Assault on the Ballot: Florida law makes it harder for grassroots organizations to assist historically disenfranchised voters

Trust is hard to build. Especially in Jacksonville, Florida, where Sheila Singleton and Rosemary McCoy live. You have to walk a lot of staircases, get past a lot of fear.

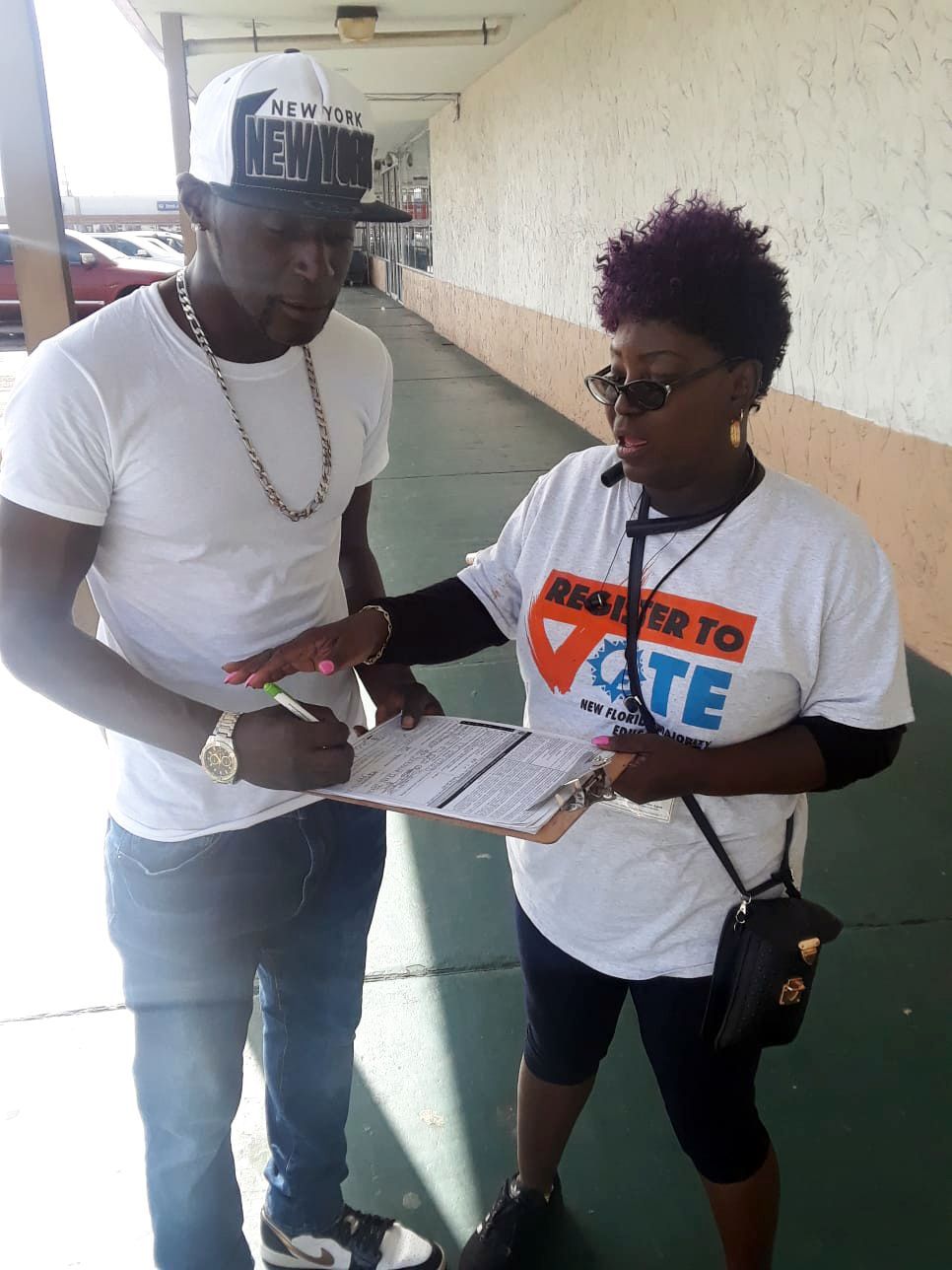

But that does not deter McCoy, 63, Singleton, 59, or the handful of volunteers they have recruited to their small voting outreach and advocacy organization. They ply the corridors of bus terminals, stand outside grocery stores and knock on doors to convince people to register to vote. Every day, they make progress against skepticism and people who are too mistrustful, too scared or too busy just trying to get by to believe that their voice can make a difference.

That’s why, when Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed Senate Bill 90 (SB 90) in May, in a “Fox News exclusive,” live-streamed event that excluded all other media, McCoy and Singleton decided that they had endured enough. SB 90 is modeled off the broad, restrictive and unnecessary voting legislation cropping up in 2021 state legislatures from Texas to Georgia in the wake of historic voter turnout in 2020.

Among other things, SB 90 requires civic organizations engaged in voter registration activities to provide misleading information to voters that the organizations “might not” submit their registration application on time. This disclaimer will make the trusted voter relationship work McCoy and Singleton have long done to advance voting rights in Florida even harder.

That is why their organization, Harriet Tubman Freedom Fighters Corp., filed a lawsuit challenging SB 90. The complaint, filed in June on behalf of the organization by Fair Elections Center and the Southern Poverty Law Center, challenges the law’s misleading disclaimer and disclosure requirements. It alleges that the law is void because of its vagueness under the due process clause of the 14th Amendment, that the disclaimer is government-compelled speech in violation of the First Amendment, and that it prevents organizations from exercising their expressive and associational rights guaranteed by the First Amendment.

“We are working so hard to earn trust,” McCoy said of their voter registration efforts. “And when we are out in the field, we see that often people don’t believe the system works for them. We are out there encouraging them, talking about issues, educating them on civic engagement, and this right here, it just throws a wrench in everything we are trying to do. ... Now the individual is looking at the canvasser and saying, ‘Wait a minute, you are telling me that you might just throw my registration away? So why should I give you this? Why should I bother at all?’”

The provision that targets third-party voting organizations has not gotten as much attention as some other elements of the 48-page law. Passed in the wake of the 2020 presidential election under the pretext of addressing unfounded and unspecified concerns about election integrity, SB 90 makes a slew of changes to Florida election law.

It requires voters to provide a state ID number or the last four digits of their Social Security number to obtain a mail ballot, providing no alternative if a voter has neither identification number. It shortens the time period during which a voter can remain on the state’s vote-by-mail list, which entitles them to receive a mail ballot automatically. It modifies rules for observers in ways that could disrupt election administration and restricts private individuals and entities from providing things like rides, chairs, umbrellas, food and water to voters waiting in line to cast a ballot.

But by targeting third-party voter registration organizations, which often more effectively reach first-time voters or people who are less inclined to cast a ballot – and these voters played an essential role in the 2020 election – the law cuts at the heart of the democratic system. By making voter registration more difficult, it is harder to put ballots into the hands of all eligible voters.

The lawsuit also seeks to protect voting rights for people with disabilities. The Paralyzed Veterans of America Florida and the Paralyzed Veterans of America Central Florida chapters, along with voters who have disabilities, last month joined the lawsuit, adding a new claim to ensure that all Florida voters with disabilities can exercise their right to cast ballots by mail with the assistants of their own choosing, as protected by federal voting rights laws.

‘A disturbing pattern’

“Florida has a disturbing history of policing third-party voter registration organizations with unconstitutional laws and regulations,” said Emma Bellamy, a senior staff attorney for the SPLC’s Voting Rights Practice Group and the lead lawyer on the lawsuit. “Senate Bill 90 is no different, and it also fits into a disturbing new pattern, in 2021, of the Florida government interfering with individuals’ and organizations’ constitutional right to free speech and expression under the First Amendment.”

The provision targeting third-party, voter registration organizations is part of a long continuum of laws by the government of Florida that target such groups, Bellamy said.

The state did not even allow such organizations to exist until 1995. Even then, Florida only did so because, in 1993, Congress passed the National Voter Registration Act, which – like the federal protection of voting rights that Congress is considering today in the For The People Act – established federal standards to expand the means of voter registration, as well as increase and protect registered voters.

After federal law forced Florida to allow third-party voter registrations, the state imposed a series of restrictions on such groups that intensified after each close presidential election. For example, after the 2000 and 2008 presidential elections, Florida passed a law restricting and penalizing third-party voter registration organizations.

Federal courts subsequently ruled that some of these restrictions were unconstitutional. But many of these restrictions are still in effect today. They include requiring third-party voter registration organizations to register with the state before they can begin activities, to renew their registrations annually, and to divulge names and contact information for their officers and employees, which the state publishes on a free online portal. The organizations would also be required to pay fines if they failed to deliver a voter registration form within a certain time period.

So even before the passage of SB 90, Bellamy said, Florida had imposed restrictions on voter registration organizations. Those restrictions presented unusual government oversight and obstacles.

Yet this is not McCoy and Singleton’s first encounter with tough obstacles. As Black women whose lives were derailed decades ago by minor felonies, they both served time in jail and both understand all too well the fear, mistrust, discrimination and despair that can keep people from voting. Like thousands of others in Florida, they owe fees, fines and restitution associated with their convictions that deny them the right to vote under Florida law.

In 2019, DeSantis signed a bill into law requiring people convicted of felonies to pay all legal financial obligations related to their convictions before they could vote. McCoy and Singleton are both plaintiffs in a separate lawsuit filed by the SPLC – McCoy vs. DeSantis – which argues that tying the right to vote for people with felony convictions to their ability to pay back such financial obligations is a violation of their constitutional rights, including – for women – their right to vote under the 19th Amendment.

But these women, both grandmothers with a keen sense that their efforts may help their kids and grandkids, are determined to give others the voice that only the ballot can guarantee. Since they founded their voter registration organization and named it for the 19th century icon who ferried enslaved people to freedom, they have not let up.

McCoy, a Navy veteran and former real estate agent, and Singleton, a certified nurse’s assistant before she was incarcerated, go to assisted living facilities and bus terminals and stand outside neighborhood shops with clipboards and pamphlets on the importance of participating in elections. They wear T-shirts emblazoned with an image of Harriet Tubman that Singleton made in several colors and styles. Aided by a handful of volunteers they hope will swell to dozens before the 2022 midterm elections, they plan to find voters where they are, emphasize the importance of making their voices heard at the ballot box and empower them to exercise their voting rights.

For their grassroots voter outreach and advocacy efforts, Harriet Tubman Freedom Fighters Corp. was awarded a grant of $50,000 by the Vote Your Voice campaign earlier this year. This campaign is investing up to $30 million from the SPLC’s endowment to engage voters and increase voter registration, education and participation.

‘In it to win it’

But the new state law, McCoy and Singleton say, will slow them down. It will force them to invest more time and resources training staff and volunteers, ensure that materials they print and give canvassers meet SB 90’s disclaimer and disclosure requirements and make each interaction with potential voters longer, more confusing and more difficult. Although McCoy and Singleton, and many of their staff and volunteers, are experienced and effective canvassers – having worked for years for larger voting organizations – they believe the new disclaimer and disclosure requirements will sow doubt among potential voters and hamper their efforts.

Under the new provision, they and their fellow canvassers must tell each potential voter they encounter that there is no guarantee they will submit the voter registrations in a timely manner. They must, according to the law, also inform voters they contact “how to register online with the (state) division (of elections),” a mode of voter registration that is not even available to voters without a Florida driver’s license.

“When I heard of this, the first thing I thought was, evil. These are the behaviors of a person of evil spirit, these are the laws of oppressors,” McCoy said. “You don’t see Florida telling bus drivers and the pilots that they have to warn passengers, ‘We might not get you to your destination’ as they get on board.

“They keep continuing to take us backwards and we try to continue to move forward. So I think this continues to be a burden on the backs of the people. It’s like a dark shadow or a dark cloud that’s over them, and we want the light to shine.”

Singleton said the new law is clearly designed to slow down their efforts to register voters in communities of color. But she expressed confidence that they will overcome.

“We won’t be able to get as many people as we usually get because we’ve got to stop and take the time out and go through these procedures with them now,” Singleton said. “But we are in it to win it, and we are in it to be the change agents. I have to fight because there’s so many people coming up behind us. We have to do the work, and I say, we are just going to have to go out there and just work harder.”

Read more stories from the Battle for Representation: The Ongoing Struggle for Voting Rights series here.

Photo at top: Rosemary McCoy, right, discusses voting rights with a participant at The Melanin Market, a platform for minority-owned organizations such as Harriet Tubman Freedom Fighters Corp., in Jacksonville, Florida, on June 19, 2021.