Whose Heritage? Public Symbols of the Confederacy

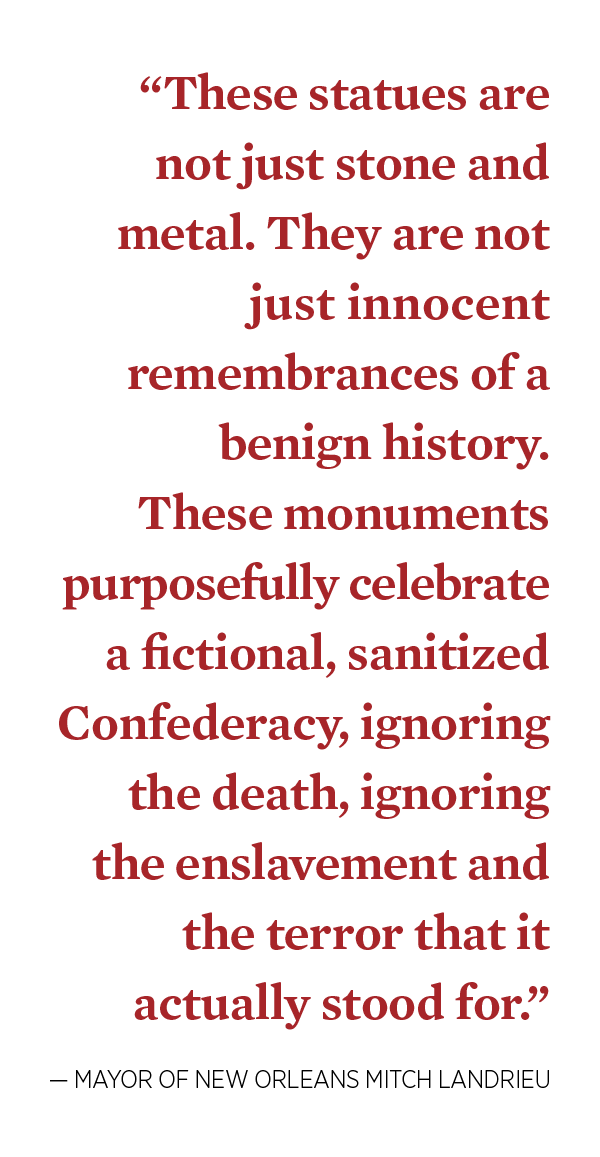

The Civil War ended 154 years ago. The Confederacy, as former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu has said, was on the wrong side of humanity.

Our public entities should no longer play a role in distorting history by honoring a secessionist government that waged war against the United States to preserve white supremacy and the enslavement of millions of people.

It’s past time for the South – and the rest of the nation – to bury the myth of the Lost Cause once and for all.

———

As of February 1, 2019, the data set, map, and online report are up to date as reported to and vetted by the SPLC. That data is available to download for research and exploration.

DOWNLOAD THE DATA

Learn more about how communities are dismantling a whitewashed history of the Confederacy and sparking a reckoning with the truth about its cruel legacy by listening to the SPLC’s podcast, Sounds Like Hate.

———

The 2015 massacre of nine African Americans at the historic “Mother Emanuel” church in Charleston, South Carolina, sparked a nationwide movement to remove Confederate monuments, flags and other symbols from the public square, and to rename schools, parks, roads and other public works that pay homage to the Confederacy.

Yet, today, the vast majority of these emblems remain in place.

In this updated edition of the 2016 report Whose Heritage?, the SPLC identifies 114 Confederate symbols that have been removed since the Charleston attack — and 1,747 that still stand.

Many of these monuments are protected by state laws in the former Confederate states.

Others are shielded by civic leaders who refuse to act in the face of a strong backlash by white Southerners who are still enthralled by the myth of the “Lost Cause” and the revisionist history that these monuments represent.

White supremacists have also taken up the cause, staging hundreds of rallies across the country to protest monument removals. We saw a dramatic display of their anger in August 2017 when hundreds of racists marched with torches and shouted Nazi slogans in Charlottesville, Virginia, where a young, anti-racist counterprotester was killed.

President Donald Trump has sided with those who want to continue honoring the Confederacy, calling the removal of “beautiful” monuments “foolish” and tweeting that it is “[s]ad to see the history and culture of our great country being ripped apart.”

In New Orleans, a multicultural city steeped in Southern history, the political leadership took the opposite tack. In 2017, then-Mayor Mitch Landrieu powerfully defended the city’s removal of three prominent monuments and denounced the “false narrative” promoted by the “Cult of the Lost Cause.” That cult, he said, “had one goal — through monuments and through other means — to rewrite history to hide the truth, which is that the Confederacy was on the wrong side of humanity.”

We encourage communities across the country to reflect on the true meaning of these symbols and ask the question: Whose heritage do they truly represent?

After being indoctrinated online into the world of white supremacy and inspired by a racist hate group, Dylann Roof told friends he wanted to start a “race war.” Someone had to take “drastic action” to take back America from “stupid and violent” African Americans, he wrote.

Then, on June 17, 2015, he attended a Bible study meeting at the historic Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and murdered nine people, all of them black.

The act of terror shocked America with its chilling brutality.

But Roof did not spark a race war. Far from it.

Instead, when photos surfaced depicting the 21-year-old white supremacist with the Confederate battle flag — including one in which he held the flag in one hand and a gun in the other — Roof ignited something else entirely: a grassroots movement to remove the flag from public spaces.

In what seemed like an instant, the South’s 150-year reverence for the Confederacy was shaken. Public officials responded to the national mourning and outcry by removing prominent public displays of its most recognizable symbol.

It became a moment of deep reflection for the nation — and particularly for a region where the Confederate flag is viewed by many white Southerners as an emblem of their heritage and regional pride despite its association with slavery, Jim Crow and the violent resistance to the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

The moment came amid a period of growing alarm about the vast racial disparities in our country, seen most vividly in the deaths of unarmed African Americans at the hands of police.

Under intense pressure, South Carolina officials acted first, passing legislation to remove the Confederate flag from the State House grounds, where it had flown since 1961. In Montgomery, Alabama — a city known as the Cradle of the Confederacy — the governor acted summarily and without notice, ordering state workers to lower several versions of Confederate flags that flew alongside a towering Confederate monument just steps from the Capitol.

The movement quickly began to focus on symbols beyond the flag. In Memphis, the city council voted to remove a statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest, the Confederate general who oversaw the massacre of black Union soldiers and became a Ku Klux Klan leader after the Civil War. Months later, after a heated debate in December, the New Orleans City Council voted to remove three Confederate statues and another commemorating a bloody white supremacist rebellion against the city’s Reconstruction government in 1874.

Across the South, communities began taking a critical look at many other symbols honoring the Confederacy and its icons — statues and monuments; city seals; the names of streets, parks and schools; and even official state holidays.

Now, three years after the Charleston massacre, more than 100 monuments and other symbols of the Confederacy have been removed. But far more remain. In this updated survey, the Southern Poverty Law Center identified 1,747 Confederate monuments, place names and other symbols still in public spaces, both in the South and across the nation.* These include:

- 780 monuments, more than 300 of which are in Georgia, Virginia or North Carolina;

- 103 public K-12 schools and three colleges named for Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis or other Confederate icons;

- 80 counties and cities named for Confederates;

- 9 observed state holidays in five states; and

- 10 U.S. military bases.

Critics may say removing a flag or monument, renaming a military base or school, or ending a state holiday is tantamount to “erasing history.” In fact, across the country but mostly in the South, Confederate flag supporters held more than 350 rallies in the six months after the Charleston attack. In Charlottesville, Virginia, the city council’s vote to remove statues of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson sparked several demonstrations, including the deadly protest on Aug. 11-12, 2017, one of the largest white supremacist rallies in decades.

But the argument that the Confederate flag and other displays represent “heritage, not hate” ignores the near-universal heritage of African Americans whose ancestors were enslaved by the millions in the South. It trivializes their pain, their history and their concerns about racism — whether it’s the racism of the past or that of today.

And it conceals the true history of the Confederate States of America and the seven decades of Jim Crow segregation and oppression that followed the Reconstruction era.

There is no doubt among reputable historians that the Confederacy was established upon the premise of white supremacy and that the South fought the Civil War to preserve its slave labor. Its founding documents and its leaders were clear. “Our new government is founded upon … the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition,” declared Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens in his 1861 “Cornerstone speech.”

It’s also beyond question that the Confederate flag was used extensively by the Ku Klux Klan as it waged a campaign of terror against African Americans during the civil rights movement and that segregationists in positions of power raised it in defense of Jim Crow. George Wallace, Alabama’s governor, unfurled the flag above the state Capitol in 1963 shortly after vowing “segregation forever.” In many other cases, schools, parks and streets were named for Confederate icons during the era of white resistance to equality.

Despite the well-documented history of the Civil War, legions of Southerners still cling to the myth of the Lost Cause as a noble endeavor fought to defend the region’s honor and its ability to govern itself in the face of Northern aggression. This deeply rooted but false narrative is the result of many decades of revisionism in the lore and even textbooks of the South that sought to create a more acceptable version of the region’s past. Confederate monuments and other symbols are very much a part of that effort.

As a consequence of the national reflection that began in Charleston, the myths and revisionist history surrounding the Confederacy may be losing their grip in the South.

Yet, for the most part, the symbols remain.

The effort to remove them is about more than symbolism. It’s about starting a conversation about the values and beliefs shared by a community.

It’s about understanding our history as a nation.

And it’s about acknowledging the injustices of the past as we address those of today.

Download a larger version of this image.

The dedication of Confederate monuments and the use of Confederate names and other iconography began shortly after the Civil War ended in 1865. But two distinct periods saw significant spikes.

The first began around 1900 as Southern states were enacting Jim Crow laws to disenfranchise African Americans and re-segregate society after several decades of integration that followed Reconstruction. It lasted well into the 1920s, a period that also saw a strong revival of the Ku Klux Klan. Many of these monuments were sponsored by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The second period began in the mid-1950s and lasted until the late 1960s, the period encompassing the modern civil rights movement.

While new monument activity has died down, since the 1980s the Sons of Confederate Veterans has continued to erect new monuments.

It’s difficult to live in the South without being reminded that its states once comprised a renegade nation known as the Confederate States of America. Schools, parks, streets, dams and other public works are named for its generals. Courthouses, capitols and public squares are adorned with resplendent statues of its heroes and towering memorials to the soldiers who died. U.S. military bases bear the names of its leaders. And, speckling the Southern landscape are thousands of Civil War markers and plaques.

Note: The map below includes symbols and monuments that have been removed. To view only the active symbols, uncheck the "Removed symbols" box.

The South even has its own version of Mount Rushmore — the Confederate Memorial Carving, a three-acre, high-relief sculpture depicting Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson on the face of Stone Mountain near Atlanta.

There is nothing remotely comparable in the North to honor the winning side of the Civil War.

For decades, those opposed to public displays honoring the Confederacy raised their objections, but with little success. A notable exception was a Southern Poverty Law Center suit that, relying on an obscure state law, led to the removal of the Confederate battle flag from the Alabama Capitol in 1993. Another was a 2000 compromise between South Carolina lawmakers and the NAACP that moved the flag from its perch above the Capitol dome to a monument on the State House grounds.

But everything changed on June 17, 2015 — just five days short of the 150th anniversary of the last shot of the Civil War.

That day in June, a white supremacist killed nine African-American parishioners at the “Mother Emanuel” church in Charleston, a place of worship renowned for its place in civil rights history.

As the nation recoiled in horror, photos showing the gunman with the Confederate flag were discovered online. Almost immediately, political leaders across the South were besieged with calls to remove the flag and other Confederate symbols from public spaces.

In the weeks that followed, it became clear that hundreds of public entities ranging from small towns to state governments across the South paid homage to the Confederacy in some way. But there was no comprehensive database of such symbols, leaving the extent of Confederate iconography supported by public institutions largely a mystery.

In an effort to assist the efforts of local communities to re-examine these symbols, the SPLC launched a study to catalog them. For the final tally, the researchers excluded thousands of monuments, markers or other tributes that were on or in battlefields, museums, cemeteries and other places that are largely historical in nature. In this second edition of the report, the SPLC has identified monuments and symbols not included in the first report and removed those reported erroneously.

Here are the most salient findings:

1. There are more than 1,700 symbols of the Confederacy in public spaces.

The study identified 1,747 publicly sponsored symbols honoring Confederate leaders, soldiers or the Confederate States of America in general. These include monuments and statues; flags; holidays and other observances; and the names of schools, highways, parks, bridges, counties, cities, lakes, dams, roads, military bases and other public works. Many of these are prominent displays in major cities and at state capitols; others, like the Stonewall Jackson Volunteer Fire and Rescue Department in Manassas, Virginia, are little known.

Among the approximately 184 individual Confederates* honored with monuments and place names, Robert E. Lee is by far the most prominent, with a total of 230. He’s followed by Jefferson Davis (152), Stonewall Jackson (112), P.G.T. Beauregard (57) and J.E.B. Stuart (49).

Sign our petition to tell lawmakers to remove symbols honoring Jefferson Davis from public spaces.

2. There are 103 public K-12 schools and three colleges named after prominent Confederates.

Of the 103 public schools and three colleges named for Confederates leaders, those honoring Robert E. Lee are the most numerous (42), followed by Stonewall Jackson (15), Jefferson Davis (11), Nathan Bedford Forrest (8) P.G.T. Beauregard (7) and John Reagan (6).

At least 34 of these schools/colleges were built or dedicated from 1950 to 1970, broadly encompassing the era of the modern civil rights movement.

The vast majority are in the states of the former Confederacy, though Robert E. Lee Elementary in East Wenatchee, Washington, is an interesting outlier. And, until their names were changed in 2016, two elementary schools in California (Long Beach and San Diego) were named for Lee. The Long Beach school was renamed in honor of a local labor activist.

3. There are nearly 800 Confederate monuments and statues on public property throughout the country, the vast majority in the South.

The study identified 780 monuments at county courthouses, town squares, state capitols and other public venues. The majority (604) were dedicated before 1950. Twenty eight were dedicated between 1950 and 1970. Thirty-four were dedicated after 2000.

Many of these are memorials to Confederate soldiers, typically inscribed with colorful language extolling their heroism and valor, or, sometimes, the details of particular battles or local units. Some go further, however, to glorify the Confederacy’s cause. For example, in Abbeville, South Carolina, a monument erected in 1906 is inscribed with a poem that reads, in part: “The world shall yet decide, in truth’s clear, far-off light, that the soldiers who wore the gray, and died with Lee, were in the right.”

Three states stand out for having far more monuments than others: Georgia (114), Virginia (110) and North Carolina (97). But the other eight states that seceded from the Union have their fair share: Texas (68), Alabama (60), South Carolina (58), Mississippi (52), Tennessee (43), Arkansas (41), Louisiana (32) and Florida (26).

These monuments are found in a total of 23 states and the District of Columbia. Outside of the seceding states, the states with the most are Kentucky (24), Missouri (13) and West Virginia (9). Monuments are also found in states far from the Confederacy, including California (3) and Arizona (4). There was even a Confederate monument in Massachusetts, a stalwart of the Union during the Civil War, but it was removed from Georges Island in Boston Harbor in 2017.

4. There were two major periods in which the dedication of Confederate monuments and other symbols spiked — the first two decades of the 20th century and during the civil rights movement.

Southerners began honoring the Confederacy with statues and other symbols almost immediately after the Civil War. The first Confederate Memorial Day, for example, was dreamed up by the wife of a Confederate soldier in 1866. That same year, Jefferson Davis laid the cornerstone of the Confederate Memorial Monument in a prominent spot on the state Capitol grounds in Montgomery, Alabama.

But two distinct periods saw a significant rise in the dedication of monuments and other symbols.

The first began around 1900, amid the period in which states were enacting Jim Crow laws to disenfranchise the newly freed African Americans and re-segregate society. This spike lasted well into the 1920s, a period that saw a dramatic resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, which had been born in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War.

The second spike began in the early 1950s and lasted through the 1960s, as the civil rights movement led to a backlash against deseregationists.

5. The Confederate flag maintains a publicly supported presence in at least five Southern states.

In 2015, Confederate flags were removed from the capitol grounds of South Carolina and Alabama following the Charleston church massacre. However, the survey identified seven public places in five former Confederate states where the flag still flies or is represented.

The most prominent is the Mississippi state flag, adopted amid the onset of Jim Crow in 1894. It conspicuously incorporates the Confederate battle flag into its design. In addition, emblems that adorn the uniforms of Alabama state troopers contain a likeness of the flag.

Also, there are four county courthouses where the flag still flies: Grady and Rabun counties in Georgia, Carroll County in Mississippi, and Walton County in Florida.

6. Ten major U.S. military bases are named in honor of Confederate military leaders.

All of the 10 military bases named for Confederate leaders are located in the former states of the Confederacy. They are Fort Rucker (Gen. Edmund Rucker) in Alabama; Fort Benning (Brig. Gen. Henry L. Benning) and Fort Gordon (Maj. Gen. John Brown Gordon) in Georgia; Camp Beauregard (Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard) and Fort Polk (Gen. Leonidas Polk) in Louisiana; Fort Bragg (Gen. Braxton Bragg) in North Carolina; Fort Hood (Gen. John Bell Hood) in Texas; and Fort A.P. Hill (Gen. A.P. Hill), Fort Lee (Gen. Charles Lee) and Fort Pickett (Gen. George Pickett) in Virginia.

7. Eleven states have 23 Confederate holidays or observances in their state codes; nine of those were paid holidays in 2018.

In 11 states, 23 Confederate holidays or observances are written into the state code, but only nine of those holidays, in five states, are paid holidays for state employees.

Alabama and Mississippi each have three Confederate holidays in which state employees are given a day off, though in some cases they are combined with other holidays (Lee’s birthday, for example, is celebrated on the same day as Martin Luther King Day).

The nine holidays officially observed in 2018 are: Alabama (Robert E. Lee Day, Confederate Memorial Day and Jefferson Davis’ Birthday); Mississippi (Robert E. Lee Day, Confederate Memorial Day and Jefferson Davis’ Birthday); South Carolina (Confederate Memorial Day); Texas (Confederate Heroes’ Day); Virginia (Lee-Jackson Day).

The other states that have Confederate holidays in their state codes are Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, North Carolina and Tennessee.

Georgia struck Lee’s birthday and Confederate Memorial Day from its official state calendar in August 2015 and replaced the names with the term “state holiday.” Arkansas in 2017 decoupled Robert E. Lee Day from Martin Luther King Day and made it a standalone, unpaid holiday marked with a gubernatorial proclamation.

Sign our petition to tell lawmakers to eliminate public holidays honoring Jefferson Davis.

8. More than 100 monuments and other Confederate symbols have been removed in 22 states, including the District of Columbia, since June 2015.

The survey identified 114 Confederate symbols removed since the Charleston massacre, including 48 monuments and three flags, and name changes for 35 schools and one college, and 10 roads. Among them was the Confederate battle flag that had flown at the South Carolina State House grounds in Columbia for 54 years.

Texas led the way (33), followed by Virginia (15), Florida (10), Tennessee (8), Georgia (6), Maryland (6), and North Carolina (4). Eighty-five removals were in former Confederate states.

Some removals were highly contentious, like in New Orleans, where the city in 2017 removed three prominent statues honoring Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis and P.G.T. Beauregard.

Sign our petition to tell lawmakers to remove symbols honoring Jefferson Davis from public spaces.

Throughout the South, thousands of historical markers have been planted along roadways and in other public spaces to commemorate some aspect of the Confederacy or its soldiers and leaders.

These markers, except in a handful of cases, are not counted in this survey. But they bear attention because of their ubiquity and because some appear to be part of a wider effort by their sponsors to mythologize and glorify the Confederacy.

Numerous markers simply pinpoint the former locations of businesses or facilities – arms factories, tanneries, and printing presses, for example – that aided the Confederacy in some way. Some memorialize relatively insignificant incidents, actions, places or facts involving Confederate military activity or leaders.

There are markers that recall the times that Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis visited a city, a marker remembering the first Confederate Memorial Day, and one marking the original location of a Confederate monument that had been moved.

In the early 1960s, during the height of the civil rights movement, the state of Texas placed a series of small stone markers in towns across the state to “memorialize Texans who served in the Confederacy.” These stones typically recount the role that local soldiers or communities played in the war, and many are placed on courthouse grounds.

Most Confederate historical markers stick with the facts, but some promote false narratives or ascribe motives to Confederate leaders that are at odds with history. In Eastman and Abbeville, Georgia, for example, nearly identical markers sponsored by the Georgia Historical Commission in 1957 recount Jefferson Davis’ final days as president of the Confederate States of America. When he was captured, the markers say, “his hopes for a new nation, in which each state would exercise without interference its cherished ‘Constitutional rights,’ forever dead.”

Typically, markers on public lands are reviewed by state or local historical commissions. In some cases, though, markers in public spaces are similar in color, shape and size to those approved by historical commissions but have no official markings to confirm that they were, in fact, sponsored or sanctioned by those bodies.

Taken in sum, Confederate markers do not provide a comprehensive look at the Civil War but rather focus narrowly on the Confederate war effort. In 2008, the Georgia Historical Society conducted a review of the more than 900 Civil War markers in the state. It found that “over 90 percent of the existing markers dealt strictly with military topics, leaving vast segments of the Civil War story untold — with almost no markers describing the war’s impact on civilians, politics, industry, the home front, African Americans, or women.”

Two heritage groups — the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) — have been particularly active in installing historical markers.

Founded in 1894, the UDC grew out of numerous women’s associations that were formed during the Civil War to support the soldiers and afterward to fund memorials, monuments and cemeteries. The group has been responsible for erecting more than 700 monuments and other memorials to the Confederacy across the South, far more than any other group, according to The Washington Post. (This study, which identified 411 monuments and 423 total symbols sponsored by the UDC, counts only those found on public land, mostly at county courthouses and other conspicuous locations. It does not include monuments at cemeteries and battlefields.)

The UDC has been accused by historians of promoting a false history and, by extension, white supremacy, particularly in its early years. After the deadly white supremacist rally in Charlottesville in August 2017, the group issued a statement, now featured prominently on its website, saying it “totally denounces any individual or group that promotes racial divisiveness or white supremacy. And we call on these people to cease using Confederate symbols for their abhorrent and reprehensible purposes.”

The SCV, formed in 1896 from the remnants of the United Confederate Veterans, is far more overt in its defense of the Confederacy and the principles for which it stood. Its website says the group “is preserving the history and legacy of these [Confederate] heroes so that future generations can understand the motives that animated the Southern Cause.” Featured on the website is a 1929 pamphlet called A Confederate Catechism, which denies that slavery or secession were causes of the Civil War. It also asserts that “[t]he negroes were the most spoiled domestics in the world.”

Southerners opposed to the removal of Confederate monuments have found plenty of support from their political leaders. Legislatures in most former Confederate states have considered — and in some cases enacted — new statutes to prevent cities and counties from removing monuments.

In 2017, for example, Alabama enacted the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act, which prohibits local governments from removing, altering or renaming monuments more than 40 years old.

The state’s attorney general in August 2017 used that law to sue the majority-black city of Birmingham for covering a Confederate monument with plywood and a tarp. Gov. Kay Ivey has called efforts to remove Confederate symbols “politically correct nonsense.”

North Carolina wasted little time enacting a law to protect monuments. In July 2015, just a month after the Charleston attack, Gov. Pat McCrory signed a bill requiring the General Assembly’s approval before a monument can be removed. “The protection of our heritage is a matter of statewide significance to ensure that our rich history will always be preserved and remembered for generations to come,” the governor said in a statement.

Five more states of the former Confederacy — Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia — already had monument protection laws on the books, some dating back decades.

In Tennessee, lawmakers in 2013 effectively hamstrung the state’s historical commission by requiring extensive paperwork and public notice. A Mississippi law protecting war memorials was written into the state code in 1972. Georgia lawmakers protected all Confederate memorials, including the giant Stone Mountain carving, in 2001 as part of a compromise to remove an image of the Confederate flag from the state flag.

Monument protection measures have also found political champions in Texas, Florida, Kentucky and Louisiana. But legislative proposals in those states, including one in Louisiana requiring a public vote, have failed.

Confederate iconography, found far and wide across the United States, is even displayed prominently in the very seat of the government that defeated the Confederacy.

The National Statuary Hall Collection in the U.S. Capitol Building currently includes eight statues that honor high-ranking political leaders and military officers of the Confederate States of America. One of those is slated for replacement.

In all, the collection comprises 100 statues, two sponsored by each state to memorialize notable people from their past.

The Confederates honored in Statuary Hall are: Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy (Mississippi); Gen. James Z. George (Mississippi); Gen. Wade Hampton III (South Carolina); Gen. Robert E. Lee (Virginia); Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith (Florida); Alexander Stephens, vice president of the Confederacy (Georgia); Col. Zebulon Baird Vance (North Carolina); and Gen. Joseph Wheeler (Alabama).

Earlier this year, the Florida Legislature voted to remove its statue of Smith and replace it with one to honor civil rights activist and educator Mary McLeod Bethune. She will be the first African American with a state-commissioned statue in Statuary Hall.

In 2009, Alabama removed its statue of Lt. Col. Jabez Curry, an Army officer and member of the First Confederate Congress, and replaced it with Helen Keller.

In addition to its statue of Vance, North Carolina honors Charles Brantley Aycock, who was raised in the aftermath of the Civil War and became governor on a virulently racist platform during the era when Jim Crow laws were being implemented across the South.

Aycock is most famous for delivering his 1903 “negro problem” speech, in which he defended the absolute disenfranchisement of African Americans, in circumvention of the recently adopted 15th Amendment. Aycock said: “If manifest destiny leads to the seizure of Panama, it is certain that it likewise leads to the dominance of the Caucasian. When the negro recognizes this fact we shall have peace and good will between the races.”

In 2015, North Carolina state lawmakers voted to remove Aycock and replace him with a statue of evangelist Billy Graham. At the time, Graham was still alive and therefore ineligible. As for now, Aycock’s statue remains.

West Virginia was not a state during the Confederacy, but it honors a former state politician who served in the Confederate Army. John Kenna, however, was not known for his service in the Confederacy. He was an enlisted soldier before going on to serve in the U.S. House and Senate from West Virginia.

This report was compiled by using a variety of public and private datasets, as well as information submitted by the public, to identify monuments as well as place names and other symbols of the Confederacy found on public property or supported by public entities.

Public sources included the U.S. Geological Survey, the National Center for Education Statistics, the National Park Service, the National Register of Historic Places, and the Smithsonian Institution’s Art Inventory.

The researchers also reviewed news accounts and state and local government resources, such as state historical commissions and similar agencies. The information available through these sources was inconsistent across states. Some states, such as North Carolina, have comprehensive databases, while others, such as Louisiana, have very limited information.

Private resources were used extensively for this edition. One of the most well-documented online sources of data on historical monuments is Waymarking, a membership-based database of locations in which members can post places and objects that they have visited. The public can search this database, and each entry includes a photograph and GPS coordinates. The Historical Marker Database is another source of information with entries submitted by the public and confirmed by an editor.

Excluded from this count in this survey were thousands of monuments, markers, names or other tributes located on or within battlefields, museums, cemeteries or other places that are largely historical in nature. Markers that appeared to be approved by historical commissions were also excluded.

Although some Confederate officers went on to have distinguished post-Civil War careers — including serving as governors and senators — monuments or other tributes that recognize their Confederate war service are included in the count. If the tribute specifically honors an aspect of their post-Civil War life, it is not included. Several tributes were dedicated before the Civil War; we decided to include them because the men they honor are known mostly today for their role in the Confederacy.

School names

School and school board websites were used to confirm the origins of school names (as were city and county websites to confirm those name origins). In a few instances, confirmation was not possible and schools were included or excluded based on the best evidence available. Schools were contacted directly by email or phone to confirm whether they had plans to change their name. In some instances, school boards had voted to change a name but had not set a date for the change. These schools were included. Finally, our findings on schools was cross-referenced with an April 2018 report by Education Week on schools named for Confederate leaders.

Roadways

The locations of roadways were verified on Google maps. They were determined to be named for Confederates if a person’s full name was used, e.g. Jefferson Davis Avenue; if the last name or nickname matches a prominent Confederate hero and is not commonplace, e.g. Stonewall and Forrest; or if the name is non-distinct, e.g. Johnston and Hampton, but the street is part of a cluster of streets named for Confederates or abuts a parcel of land that contains a Confederate monument. In several instances, names spelled incorrectly, such as Forrest spelled as “Forest” and Stuart spelled as “Stewart,” were included because they were part of clusters.

Monuments

Monuments that were added to this edition of the report were discovered through crowd-sourcing, recent newspaper articles, new city and state surveys of monuments on public land, and private sources. The SPLC initiated an online call for submissions in April 2016 as a way of capturing symbols that were missed or reported in error in the first edition. Readers submitted 853 different entries through an online form (most of which were already in the first edition), as well as corrections for symbols that were erroneously included in the first edition.

Removals

Since the 2015 Charleston church massacre, many communities have removed Confederate monuments or renamed schools bearing Confederate names. In this edition, researchers noted the year of such removals and name changes after confirming the change with at least one source. Also, in an attempt to create the most comprehensive dataset of current and past Confederate monuments, we included monuments and other symbols that were removed before 2015. A monument was only considered removed/name changed if the action had already been taken or if a firm date had been established.

Markers vs. Monuments

In this report there are 45 monuments with “marker” in their name. They are classified as monuments because they are stone objects that cannot be easily removed (they are not markers in the traditional sense, i.e. metal signs).

Sponsors

This edition includes information about the sponsor of each monument or other symbol, if it could be determined. This information is included in the aforementioned data sources.

That data set is available to download for research and exploration.

Please note that this data set includes removed symbols. If you filter by a single column to find out how many symbols are in a particular state, for example, it will include ones that were removed. If you only want to view symbols still on public land you will need to exclude removed ones.

If you'd like to suggest a change or addition to the data, please fill out this form.

Header photo by AP Images/Rainier Ehrhardt