‘Traveling While Black’: Virtual reality exhibit at Civil Rights Memorial Center will immerse audiences in Black experience on the road

As a young boy, Roger Ross Williams would travel with his mother, a single woman who worked as a house cleaner in a small Pennsylvania town, to visit relatives on their farm in Charleston, South Carolina.

“We would pack everything into the car, and we did it in one shot. We never stopped. I never understood why,” Williams, who grew up to be an Academy Award-winning movie director, recalled in an interview released by his film production company.

As an adult, Williams said, he realized why his mom drove 12 hours without a break: “It’s just the reality of being Black in America.”

• CRMC Event: A conversation with SPLC’s Efren Olivares

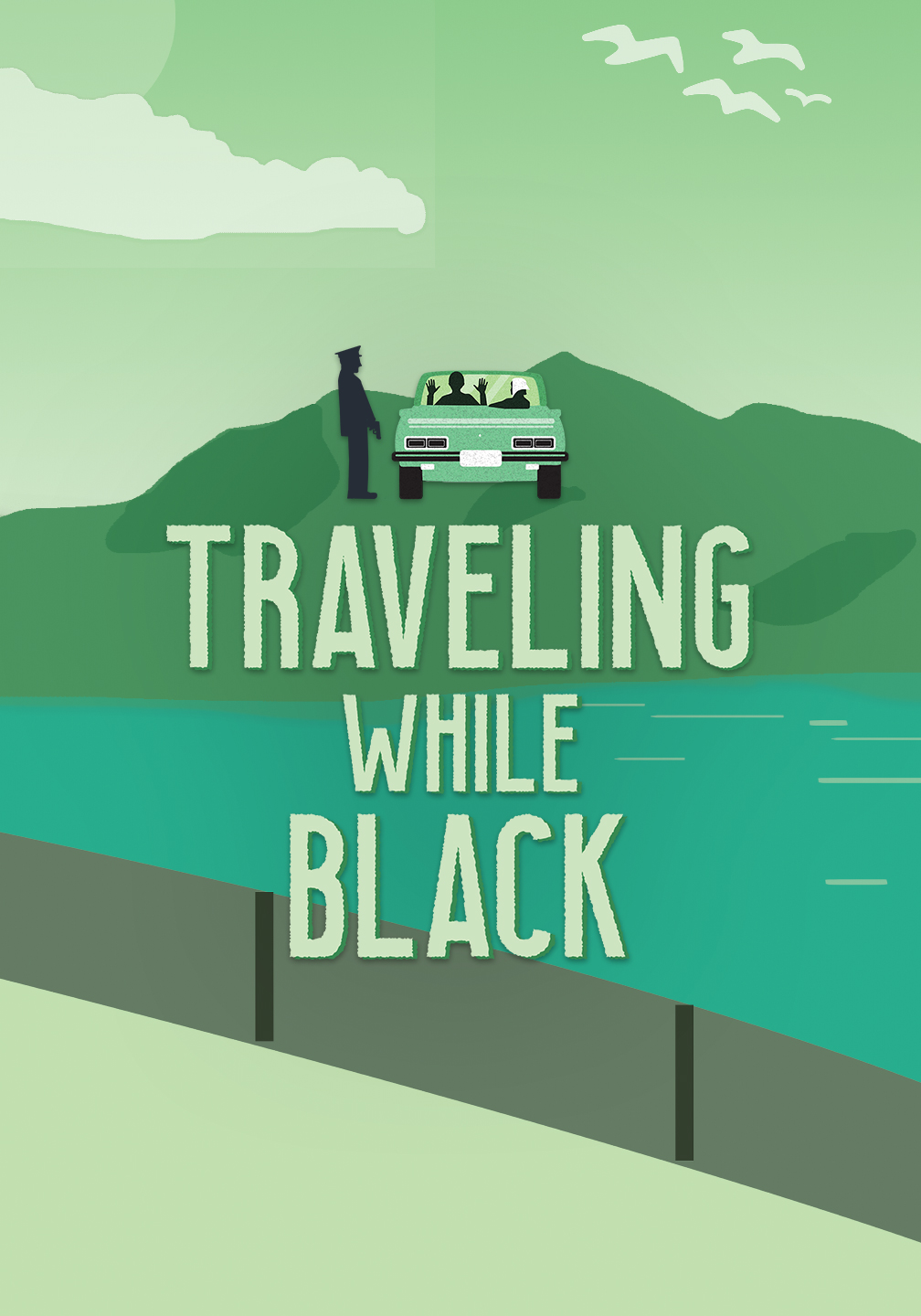

That reality is the subject of a bold, genre-bending 3D film experience directed by Williams that will be shown at the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Civil Rights Memorial Center in Montgomery, Alabama, starting Nov. 1 and running until Jan. 22, 2023. The project, “Traveling While Black,” uses high-concept documentary and virtual reality technology to immerse participants into the terrifying world of the United States during legal segregation.

Stepping into an exhibit space set up as a replica of the iconic, Black-owned restaurant Ben’s Chili Bowl in Washington, D.C., viewers will don Oculus Go headsets and, for 18 minutes, join conversations with patrons depicted through virtual reality technology who share their intimate experiences of traveling and living in the U.S. when a simple bathroom stop could be life-threatening. The virtual reality project portrays the era Williams, now 60, was born into in 1962, when the set of laws and customs known as Jim Crow were omnipresent across the American South, and when Black people faced persistent racial prejudice, price-gouging and physical violence while traveling throughout the U.S.

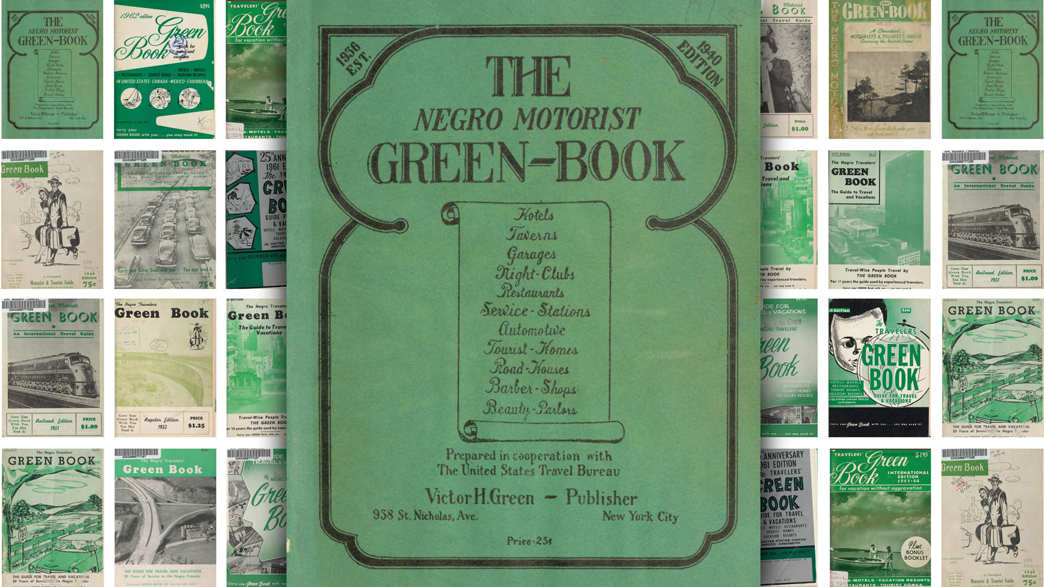

With Black travelers aware they went on the road at their peril, a guide published from 1936 to 1966 became their lifeline to finding establishments, like Ben’s Chili Bowl, where they would be welcomed rather than threatened or turned away. The guide, The Negro Motorist Green Book, was the brainchild of a Harlem, New York-based postal carrier, Victor Hugo Green, who had grown weary of the discrimination Black people faced when they left their neighborhoods. It provided a list of hotels, boarding houses, taverns, restaurants, service stations and other establishments throughout the country that served Black patrons. Traveling while Black required ingenuity and courage, and establishments like Ben’s – with its famous half-smokes, chili dogs and milkshakes, and its role at the heart of the vibrant area known as “Black Broadway” – were safe spaces, respites from the reality of white supremacy.

“Traveling While Black,” though, is explicitly designed to be more than history. It illuminates the story of segregation through personal stories, employing a collection of interviews and cinematic re-creations. The film weaves significant civil rights milestones into the experience and is designed to give participants not only a deeper historical understanding of the past, but a recognition of the depressingly enduring dangers of being Black in the United States today.

“There was a time when travel for Black people was a matter of life and death,” Williams wrote in a director’s statement that accompanies the project. “So, for me, the project started as a way to talk about this forgotten period in history. But the more I began to think about the past, I realized that not a lot has changed today … the risk we face just leaving our homes and our need for safe spaces are just as prevalent as they were during the days of the Green Book.”

Sparking conversations

Tafeni English, director of the Civil Rights Memorial Center, said that in a nation where inequality between white and Black Americans persists in almost every aspect of society and the economy, the exhibit has deep relevance and poignancy. Two years ago, the streets of American cities and towns erupted in protests after the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer cast attention on the abiding dangers Black Americans face. Showing the documentary project in Montgomery, site of the first large-scale U.S. demonstration against segregation – the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955 and 1956 – gives the project a unique power to “spark conversations around issues of race,” English said.

English said the decision to install the “Traveling While Black” exhibit at the Civil Rights Memorial Center is part of a larger mission by the SPLC to delve deep into the roots and continuing dangers of systemic racism. During the pandemic, for example, the SPLC published Movement and Space: CRMC Community Guide, a public education resource that explores the current and historic constraints on Black people’s right to move freely and occupy space. Like Williams’ virtual reality documentary, the guide is designed to encourage community groups, museum educators, high school students and others to facilitate difficult conversations about race.

“The ‘Traveling While Black’ exhibit also may in some cases change the perspective of others when they experience the treatment of others during those times,” English said. “We’re interested in being a part of the solution as it relates to the issue of race, and that begins with having honest and hard conversations with each other.”

The exhibit, English said, “will not only provide insight to what it was like for Black people to travel in the 1950s and 1960s but will draw parallels to things we’re seeing happen in our country today. We hope people will walk away further inspired to take an active role in dismantling racist systems.”

‘Lived experience’

That is exactly what happened when the exhibit, which is traveling around the country, was shown at Georgia Tech Arts, at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta last year.

During its three-month run, the exhibit drew a broad range of people, said Aaron Shackelford, director of Georgia Tech Arts. Alumni shared stories with staff. Students who had grown up only tangentially aware of the history of segregation sat rapt, transported to a world they had never experienced before. Community members joined conversations with academics, and importantly at a leading technology institution, young people studying computer design, engineering and other disciplines were exposed to a vivid example of how their particular set of skills could be used for art and for good.

“‘Traveling While Black’ was a test case for us to show our students that this is what we mean when we say that the technology they are working on has a storytelling impact that can really affect lives,” Shackelford said. “The technology of virtual reality creates the best version of oral history that I have ever seen. It allows you to sit across the table from someone. And since you are sitting there, you have to hear what they have to say. You have to engage with them in a much more powerful way than you would with any other medium.”

The proof of that engagement at Georgia Tech became, during the run of the exhibit, a wall display just outside for all to see. In a lounge area, Shackelford set up comfortable seating where visitors could write their responses and post them on a corkboard strip on the wall. Collected by the curators later and made into a short film, the responses remain poignant reminders of the exhibit’s power:

“Every human should watch this film,” one visitor wrote.

“I feel humbled and determined to contribute whatever I can to improve the human condition,” wrote another.

“I feel sad we still have to travel while Black,” wrote a third. “I hope this exhibit shifts the culture.”

“I knew that Black people were far from being safe in America, but I didn’t know the true extent,” another response card reads. “I feel frustrated and sad that we are still talking about the same problems.”

And another one admonished, “Awareness does not stop in this room.”

The message of the exhibit, Shackelford said, is one that Black people in this country do not have the luxury of forgetting.

“This really isn’t history, it is lived experience,” Shackelford said.

Photo at top: The “Traveling While Black” exhibit space replicates Ben’s Chili Bowl, a Washington, D.C., restaurant that was a safe space for Black travelers during segregation in the U.S. (Courtesy of “Traveling While Black”)