Ensuring Black Representation: Mobile, Alabama, mayor’s redistricting proposal likely violates Voting Rights Act of 1965

Like cities and towns across the country, the City of Mobile is in the midst of redrawing its city council districts to incorporate the population changes observed in the 2020 U.S. census and ensure that representatives will be responsive to the needs of the communities they serve.

By law, the city must go through this process every decade. Notable from the 2020 census, Mobile is experiencing a shift in demographics. Alabama’s fourth most populous city now has a population that is majority people of color as well as majority-Black.

Under federal law, cities are prohibited from passing districts that would dilute the voting power of Black voters. In Mobile, that means that four of the seven city council districts should be majority-Black.

Unfortunately, Mayor Sandy Stimpson’s proposed redistricting plan does not include a legally viable fourth majority-Black district, despite claims to the contrary by the mayor and his staff.

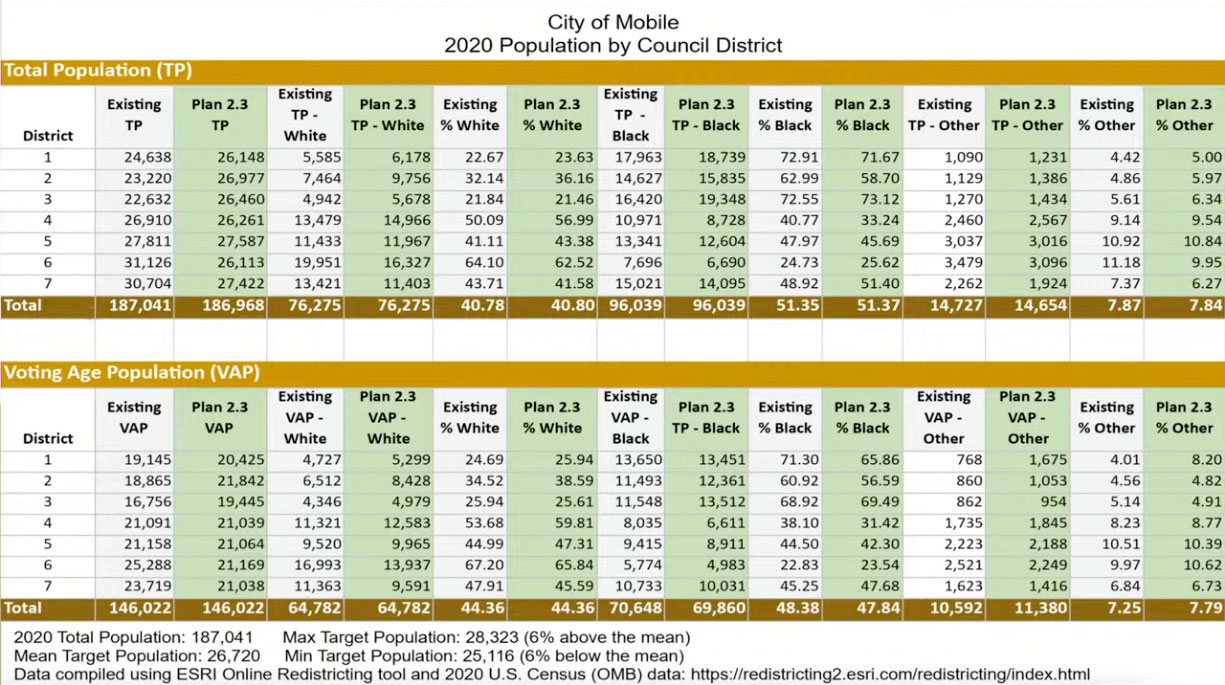

Under Stimpson’s proposal, Districts 1, 2 and 3 remain majority-Black districts. District 7 – the subject of much discussion and confusion in the community, in the press and in the mayor’s office – becomes 51.40% Black. But crucially, District 7’s Black voting-age population (“BVAP”) lags at only 47.68%.

As a result, the Black population of District 7 would not actually have the voting majority to elect a Black-preferred candidate.

That is a distinction with a huge legal difference. Instead of a lawful plan that ensures fair representation for the next decade, the mayor’s map could be an unlawful one that dilutes the political power of Black voters in violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA).

To quickly summarize, the mayor and city council have two obligations under federal law when drawing this new map: (1) fulfill the one-person, one-vote requirement rooted in the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, and (2) comply with Section 2 of the VRA.

The one-person, one-vote principle mandates that districts have substantially equal numbers of people, regardless of those people’s eligibility or desire to vote. In other words, the voting-age population in each district is irrelevant; it matters only that people are spread evenly. After all, those who can’t or don’t vote – including young people and others who are disenfranchised – still deserve representation in government.

Because about 187,041 people live in Mobile, each of the seven city council districts should contain roughly 26,720 people, with small permissible deviations.

Unlike the one-person, one-vote rule, which concerns the apportionment of total population, the test for compliance with Section 2 of the VRA looks to both age and race.

Section 2 prohibits states and localities like Mobile from drawing electoral lines that dilute Black voting strength. As the Southern Poverty Law Center explained in a letter to Stimpson and the Mobile City Council in November, Section 2 sometimes requires jurisdictions to draw additional majority-Black districts to provide Black voters an equal opportunity to elect their preferred representatives.

In Mobile’s case, that’s what the VRA demands.

The law on this is very clear: A district is only “majority-Black” for the purposes of compliance with Section 2 if Black people make up more than 50% of the district’s voting-age population. This makes sense: If the voting population isn’t a majority, how can the district give Black voters an equal opportunity to elect a candidate of choice?

If the Black voting population in District 7 falls below the majority threshold, Black voters will struggle to elect candidates of their choice to the city council – even if the total Black population (including those too young to cast a ballot) constitutes a majority.

Stimpson has committed to drawing a city council map with a fourth majority-Black district. His current proposal simply falls short of that goal. To say it succeeds is legally inaccurate at best – and duplicitous at worst.

It’s worth remembering that this is the first redistricting cycle without the protections of Section 5 of the VRA. The city has had to submit its map for federal approval by the U.S. Department of Justice since 1965. Even so, the federal courts remain open to voters seeking to enforce the VRA.

Just last week, a panel of three federal judges – appointed by presidents from both parties – found that Alabama’s congressional district map, enacted by the Alabama Legislature, likely violated Section 2 because it fails to include an additional majority-Black district. They ordered an immediate redrawing before the map could be used in any elections.

We hope Stimpson will avoid making the same mistake as the Alabama Legislature and honor not only his word to Mobilians but also his affirmative legal responsibility to comply with the Constitution and the VRA.

The table above was included in a recent redistricting town hall presentation by Mobile Mayor Sandy Stimpson.

Photo at top: An Alabama voter shows off her voting sticker after casting her ballot during the Democratic presidential primary on Super Tuesday, March 3, 2020. (Credit: Joshua Lott / AFP via Getty Images)

Caren Short is the interim deputy legal director of the SPLC’s Voting Rights Practice Group.