Alabama's War on Marijuana

Marijuana prohibition costs the state and its municipalities an estimated $22 million a year, creates a dangerous backlog at the agency that tests forensic evidence in violent crimes, and needlessly ensnares thousands of people – disproportionately African Americans – in the criminal justice system.

This report from the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law and Justice and the Southern Poverty Law Center is the first of its kind to examine the fiscal, public safety, and human toll of marijuana prohibition in the state.

Kiasha Hughes dreamed of becoming a medical assistant. Now, she works an overnight shift at a chicken plant to support her children.

Nick Gibson was on track to graduate from the University of Alabama. Now, he works at a fast-food restaurant.

Wesley Shelton spent 15 months in jail and ended up with a felony conviction – for having $10 worth of marijuana.

Like thousands of others, they’re casualties of Alabama’s war on marijuana – a war the state ferociously wages with draconian laws that criminalize otherwise law-abiding people for possessing a substance that’s legal for recreational or medicinal use in states where more than half of all Americans live.

In Alabama, a person caught with only a few grams of marijuana can face incarceration and thousands of dollars in fines and court costs. They can lose their driver’s license and have difficulty finding a job or getting financial aid for college.

This war on marijuana is one whose often life-altering consequences fall most heavily on black people – a population still living in the shadow of Jim Crow.

Alabama’s laws are not only overly harsh, they also place enormous discretion in the hands of law enforcement, creating an uneven system of justice and leaving plenty of room for abuse. This year in Etowah County, for example, law enforcement officials charged a man with drug trafficking after adding the total weight of marijuana-infused butter to the few grams of marijuana he possessed, so they could reach the 2.2-pound threshold for a trafficking charge.

Marijuana prohibition also has tremendous economic and public safety costs. The state is simply shooting itself in the pocketbook, wasting valuable taxpayer dollars and adding a tremendous burden to the courts and public safety resources.

This report is the first to analyze data on marijuana-related arrests in Alabama, broken down by race, age, gender and location. It includes a thorough fiscal analysis of the state’s enforcement costs. It also exposes how the administrative burden of enforcing marijuana laws leaves vital state agencies without the resources necessary to quickly test evidence related to violent crimes with serious public safety implications, such as sexual assault.

The study finds that in Alabama:

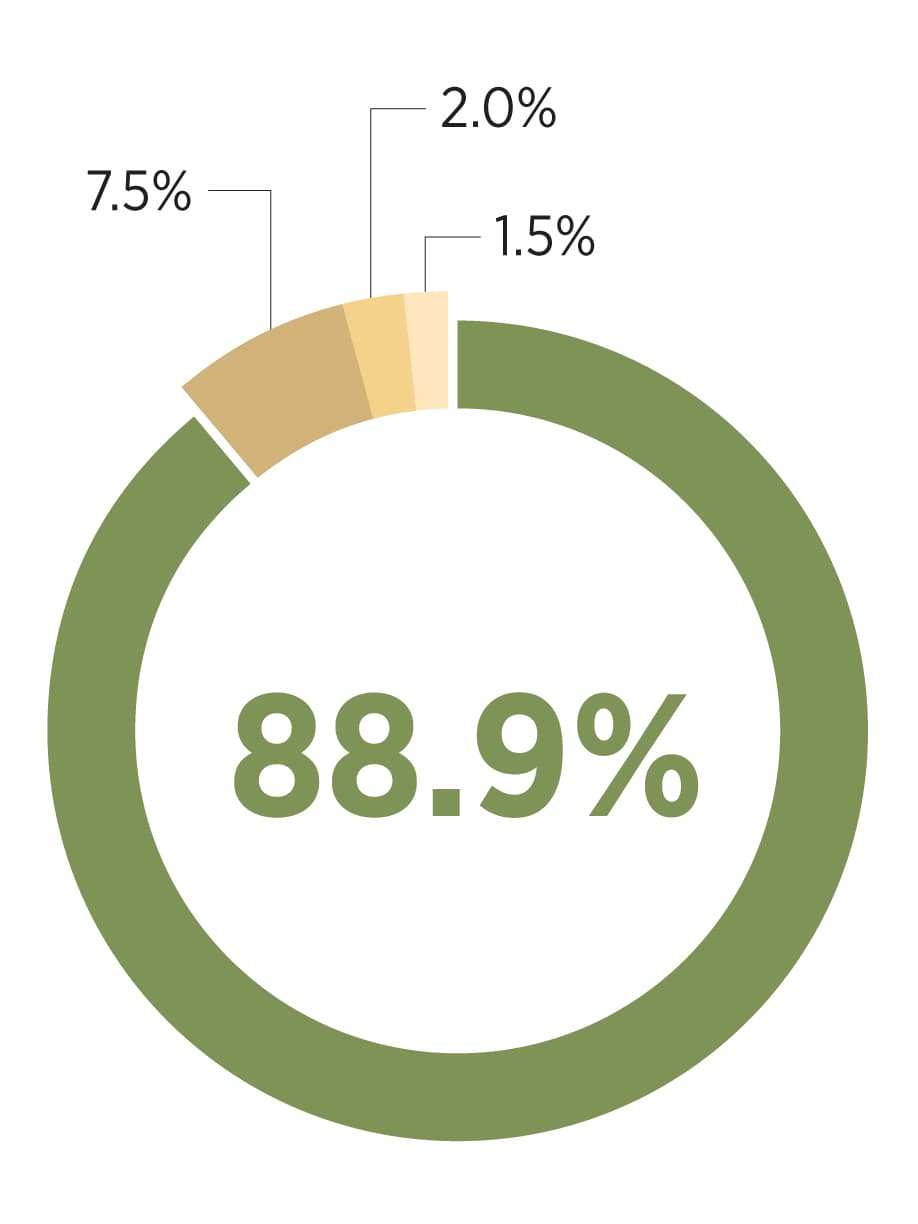

- The overwhelming majority of people arrested for marijuana offenses from 2012 to 2016 – 89 percent – were arrested for possession. In 2016, 92 percent of all people arrested for marijuana offenses were arrested for possession.

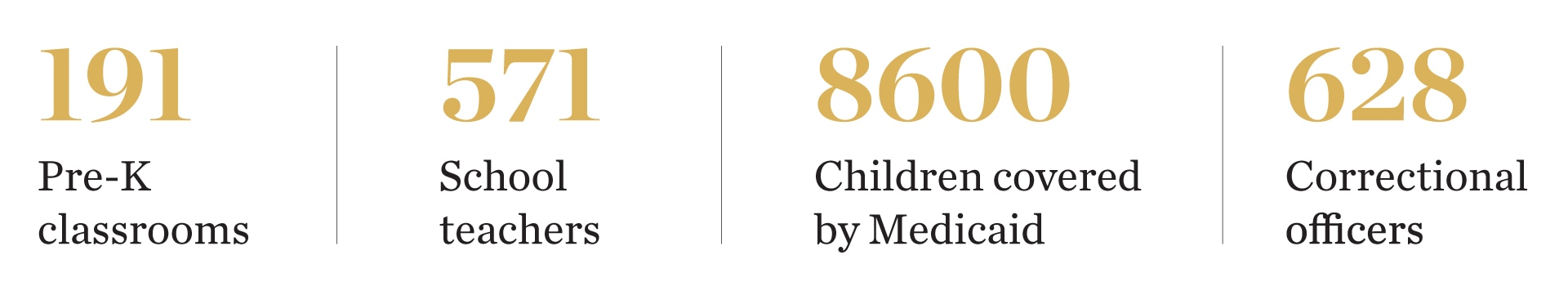

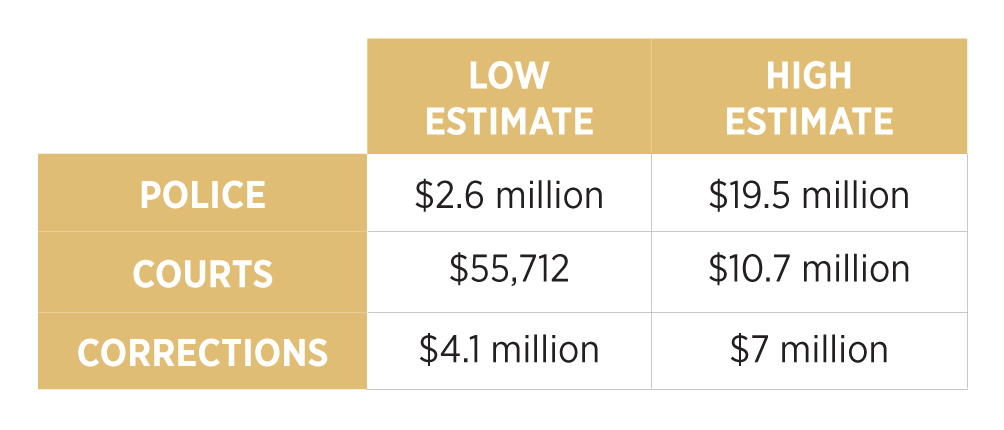

- Alabama spent an estimated $22 million enforcing the prohibition against marijuana possession in 2016 – enough to fund 191 additional preschool classrooms, 571 more K-12 teachers or 628 more Alabama Department of Corrections officers.

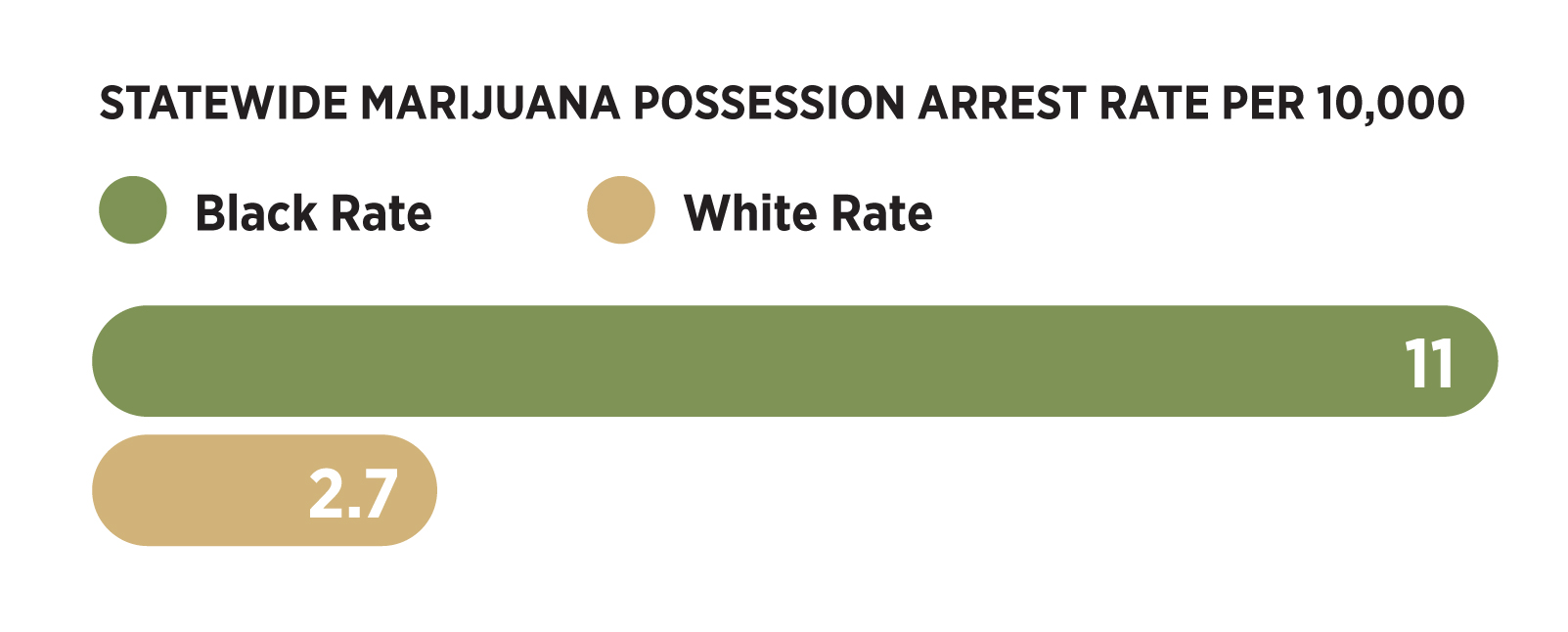

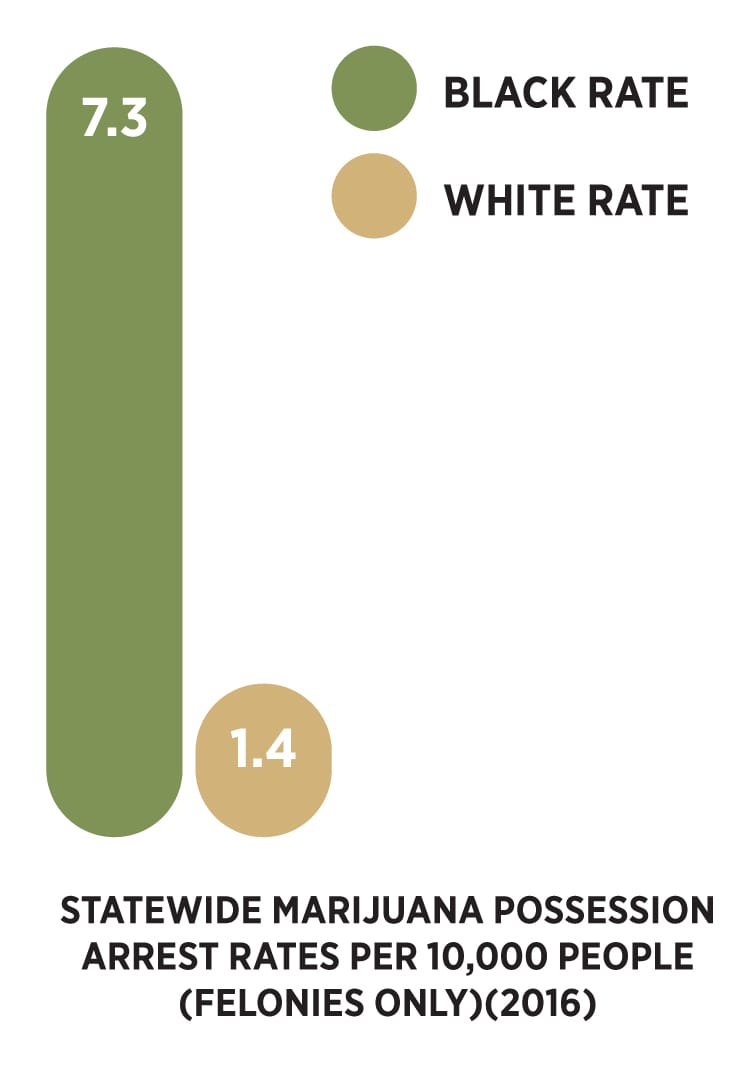

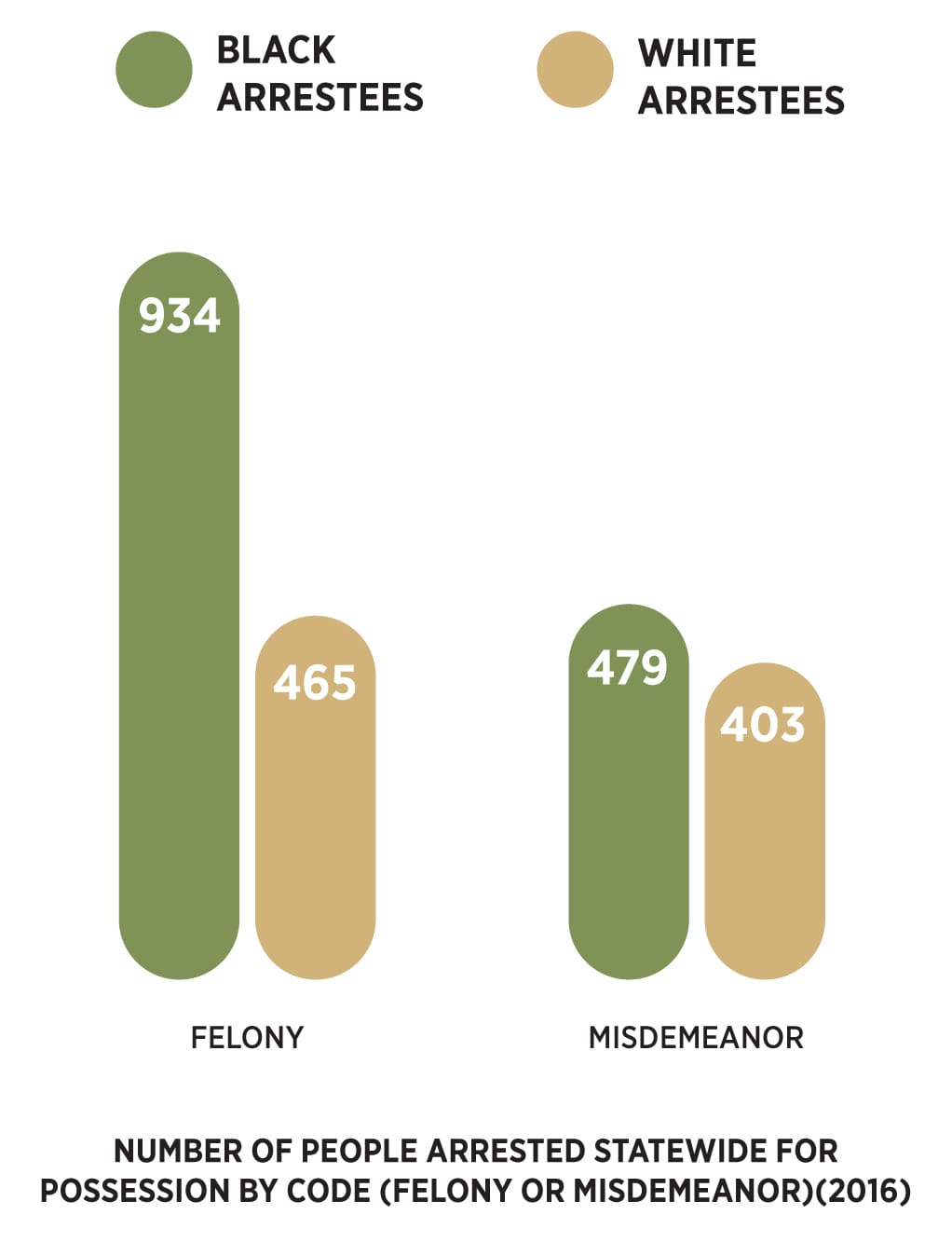

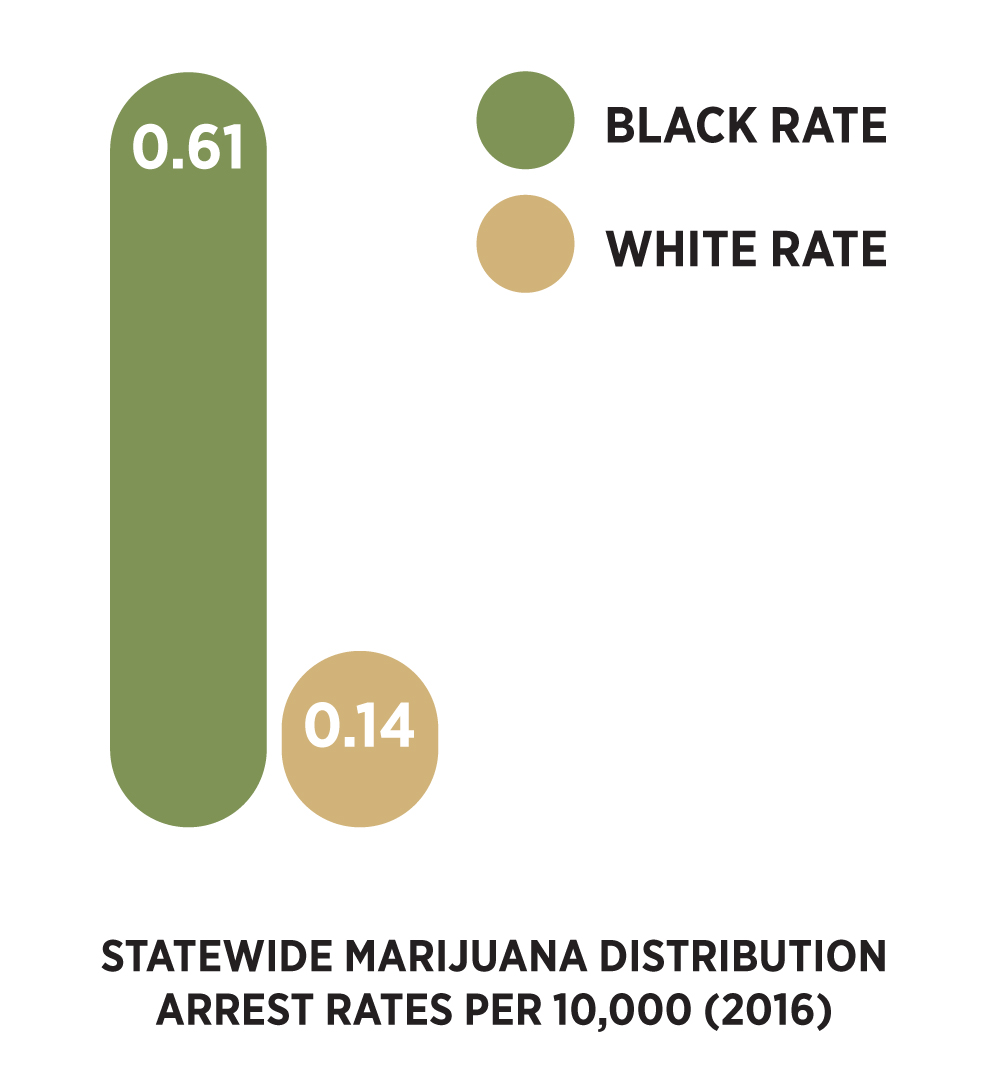

- Black people were approximately four times as likely as white people to be arrested for marijuana possession (both misdemeanors and felonies) in 2016 – and five times as likely to be arrested for felony possession. These racial disparities exist despite robust evidence that white and black people use marijuana at roughly the same rate.

- In at least seven law enforcement jurisdictions, black people were 10 or more times as likely as white people to be arrested for marijuana possession.

- In 2016, police made more arrests for marijuana possession (2,351) than for robbery, for which they made 1,314 arrests – despite the fact that there were 4,557 reported robberies that year.

- The enforcement of marijuana possession laws creates a crippling backlog at the state agency tasked with analyzing forensic evidence in all criminal cases, including violent crimes. As of March 31, 2018, the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences had about 10,000 pending marijuana cases, creating a nine-month waiting period for analyses of drug samples. At the same time, the department had a backlog of 1,121 biology/DNA cases, including about 550 “crimes against persons” cases such as homicide, sexual assault and robbery.

While Alabama continues to criminalize people who use marijuana either recreationally or medicinally, an increasing number of states have come to treat marijuana like alcohol and tobacco. Nine states and the District of Columbia now allow recreational use.

The early evidence strongly suggests that this approach benefits public safety and the criminal justice system. In those states, arrests for marijuana possession have been virtually eliminated, freeing up officers to focus on crimes of violence. Drunken-driving arrests are down as well. And, there’s no evidence of a spike in crime or increased marijuana use among youth.

These states have also enjoyed a corresponding fiscal and economic windfall. Across the country, thousands of jobs are being created where marijuana has been legalized. Three of the states where it has been legal the longest – Colorado, Washington and Oregon – have thus far collected a total of $1.3 billion in new revenue.

And, as the human toll discussed throughout this report falls disproportionately on black people, legalization offers an opportunity to begin to address the disproportionate harms that Alabama’s criminal justice system causes to its African-American population.

It’s time for Alabama to join an increasing number of states in taking a commonsense, fiscally responsible approach to marijuana policy.

Public support for legal marijuana in the United States has never been higher – 61 percent in recent polling, representing a sea change in attitudes compared with 2005, when over 60 percent were opposed. Nine states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational use, and another 13 states – including Mississippi – have reclassified small amounts as noncriminal offenses. These states, and a majority of Americans, realize that the war on marijuana is not only ineffective but a monumental waste of tax dollars and harmful to communities of color.

Despite the national and Southern state trends toward a more commonsense approach – and despite the overwhelming scientific consensus that the substance is far safer than either alcohol or cigarettes – Alabama’s marijuana laws remain both draconian and ill-defined. They result in overly harsh, unequal justice that shatters lives and drives the poor further into poverty.

The draconian nature of the state’s marijuana laws extends from possession to trafficking. Individuals charged with possessing even a small amount for personal use face a felony charge if they have a previous marijuana possession conviction. In 2015, there were 901 felony convictions in Alabama related to the possession of marijuana. It was the sixth most frequent felony offense at conviction. In the five years ending in September 2015, there were 5,014 felony marijuana possession convictions. And, while only a small fraction of these individuals will spend time in prison, they’ll nonetheless be labeled felons for the rest of their lives – a label that brings with it severe collateral consequences that continue to punish individuals even after they’ve completed their sentence.

In addition, because they are so ill-defined, Alabama’s marijuana laws are ripe for abuse by law enforcement. Drug trafficking is the only marijuana-related crime with a defined weight threshold (a minimum of 2.2 pounds). For anything under 2.2 pounds, prosecutors have the discretion to charge a person with possession for personal use, possession for a purpose other than personal use, manufacturing or distribution.

In other words, two people caught with the same amount of marijuana can be charged with different crimes. A prosecutor may choose to charge one person found with a quarter ounce of marijuana with possession for a use other than personal (a felony) and charge another person with possession for personal use only (a misdemeanor, for a first offense). This broad discretion creates wide disparities among district attorneys’ offices, resulting in uneven justice.

Even for the well-defined trafficking offense, there are serious disparities in charging decisions.

Alabama’s trafficking statute includes language allowing the government to weigh “any part of a marijuana plant” when making the weight determination. As a recent case in Etowah County shows, some law enforcement agencies have exploited such discretion.

Earlier this year, a man in Etowah County was charged with trafficking – despite possessing only a few grams of marijuana – because law enforcement included the total weight of marijuana-infused butter found on the premises, bringing the weight to slightly over the 2.2-pound threshold. Phil Sims, deputy commander of the Etowah County Drug Enforcement Unit, told a reporter, “Once that marijuana was mixed with the butter then the whole butter becomes marijuana, and that’s what we weighed.”

A police department that shares an overlapping jurisdiction with the Etowah County Sheriff’s Office said it would not add the weight of the butter to the marijuana. “You wouldn’t add the butter with that,” said a spokesperson for the Rainbow City Police Department. “It should be just the amount of marijuana.”

This case highlights not only a serious abuse of the discretion allowed under Alabama law but also the way in which the state’s marijuana policy leads to uneven justice.

Even if they didn’t result in such enforcement disparities, Alabama’s marijuana laws remain overly harsh.

For example, a person in Alabama can face a Class A misdemeanor charge (up to a year in jail and a maximum $6,000 fine) for possessing less than one ounce of marijuana and a minimum of a Class D felony for any subsequent possession offense (up to five years in prison and a maximum fine of $7,5001), regardless of the amount. The same individual with the same amount of marijuana in Mississippi would face only a civil fine ($250 maximum) for the first offense and a maximum of a misdemeanor for any subsequent possession convictions (up to six months in jail and a $1,000 maximum fine).

Marijuana laws a gateway to harsh punishment

Together, Alabama’s harsh marijuana laws have an enormous bearing on the state’s criminal justice system.

In fiscal year 2015, 265 people were committed to Department of Corrections custody for first-degree marijuana possession, according to the Alabama Sentencing Commission’s 2017 report. But while few people end up in a state prison for a possession offense, a conviction can have serious long-term consequences. For example, under the state’s Habitual Felony Offender (HFO) Act, a Class C felony marijuana possession conviction can serve as the first or second strike toward the super-sized sentence that people receive if they are convicted of a third felony. Offenders qualify for HFO sentences if they face a felony charge and have prior felony convictions. The enhancement has three primary tiers: one prior felony conviction, two prior felony convictions, and three prior felony convictions.

The impact reaches far beyond prisons, too. Many Alabamians spend time in local jails for a marijuana offense when they can't post bail. And many have lost cars, cash or other property in civil asset forfeiture cases tied to a marijuana offense. For likely thousands of people, a marijuana offense led to their first negative interaction with law enforcement, making them less likely to trust police in the future.

All these things combine to saddle more poor Alabamians with fines, fees and jail time; keep neighborhoods under police surveillance; and send more people to prison for longer. As a consequence of the failed War on Drugs, the punishments designed for marijuana offenses in the state have snowballed out of control. They simply don’t fit the supposed crimes.

Sentencing Enhancements Worsen Penalties

Sentencing enhancements, remnants of the failed War on Drugs, are a major contributor to the overly harsh and uneven justice that’s a feature of marijuana prohibition in Alabama.

These laws increase the severity of sentencing based upon factors that can be arbitrary, like if a person happens to live in public housing or near a school. For example, someone who sells marijuana in Huntsville, Tuscaloosa, Mobile, Montgomery or Birmingham is likely to do so within three miles of a public housing facility, while a person selling the same amount in a more rural part of the state is unlikely to do so. The same is true of sale near a school campus, where urban residents find themselves at greater risk of this enhancement because of nothing more than their location.

There are five main enhancements in addition to habitual felony offender status.

-

Sale of marijuana to a minor. This enhancement can apply if the person charged is over 18 and the qualifying offense consists of selling, furnishing or giving marijuana to someone under 18. It upgrades the offense to a Class A felony. Further, it prevents the court from suspending any sentence and granting probation. It can be applied to convictions for distribution/sale of marijuana, drug trafficking or drug trafficking enterprise.

-

Sale near a school. This enhancement applies when an individual is convicted of selling marijuana and the sale occurred on a campus or within a three-mile radius of the campus boundaries for any public or private school, college, university or other educational institution. It adds five years of prison to the sentence and prevents the court from granting probation. It can be applied to convictions for distribution/sale of marijuana, drug trafficking or drug trafficking enterprise. What’s more, it can be imposed in addition to other enhancements or penalties for the same offense.

-

Sale near a housing project. This enhancement applies when a marijuana sale occurred within a three-mile radius of a housing project owned by a public housing authority. It adds five years of prison to the sentence and prevents the court from granting probation. Plus, it can be imposed on top of other enhancements for the same offense. It can be applied to convictions for distribution/sale of marijuana, drug trafficking or drug-trafficking enterprise.

-

Felony firearm or deadly weapon. This applies to Class A, B and C felonies. For Class A felonies in which the offender used (or attempted to use) a firearm or deadly weapon, the punishment is a minimum of 20 years imprisonment. For Class B or C felonies in which the offender used (or attempted to use) a firearm or deadly weapon, the punishment is a minimum of 10 years. This enhancement can apply to any marijuana-related offense.

-

Drug trafficking with a firearm. This enhancement increases the already stiff punishments for drug-trafficking offenses. Five additional years of prison, to run consecutive to the original minimum mandatory prison term, and a $25,000 fine are added to the sentence. The court can neither suspend the five-year additional prison sentence nor give a probationary sentence.

Post-conviction collateral consequences

Collateral consequences are penalties an individual faces in addition to any court-imposed punishment. They include limitations on access to employment, housing, education, voting, driver’s licenses and more. For example, people who have served their sentence may still need to check the criminal history background box on an employment application.

There are both statutory and nonstatutory collateral consequences. And, because Alabama has no statewide database to help guide individuals with a criminal history through this process, individuals must often rely on social service providers and advocacy organizations to understand the limitations caused by their criminal conviction.

According to the Council of State Governments, which maintains the National Inventory on the Collateral Consequences of Conviction, of the 171 collateral consequences triggered by a marijuana conviction in Alabama, 82 are automatic.

They include 31 mandatory collateral consequences that make it more difficult for the individual to obtain employment.

Alabama law requires the automatic six-month suspension of a person’s driver’s license for anyone convicted or adjudicated guilty of trafficking, attempted trafficking, solicitation to traffic or conspiracy to traffic. If the individual lacked a driver’s license (or it was already suspended/revoked), then the penalty converts to an additional six-month delay in the issuance or reinstatement of a license.

Alabama law also allows for the suspension of a driver’s license if the person has unpaid court fines and fees, even if he or she is indigent and has no ability to pay the money.2 A recent Appleseed report found that nearly 45 percent of individuals with court debt had their licenses suspended due to nonpayment. Since Alabama lacks adequate public transportation, a valid driver’s license is essential to most adults, particularly in rural areas. Nearly everyone needs a license to get to work, take children to school or the doctor, or to buy groceries.

Penalties like this, which have nothing to do with the original offense and have no public safety justification, place unnecessary hurdles in front of people seeking to return to their communities and support their families.

A criminal record in general makes it more difficult for people who have paid their debt to society to have a fair shot at a second chance. For example, job seekers with criminal records must often check a box on an employment application that asks whether the applicant has been arrested, charged, and/or convicted of a criminal offense. Potential employers can toss these applications before the applicant ever has an opportunity to present their qualifications or rehabilitation. The criminal history box also discourages people from applying in the first place, even if they otherwise qualify for the position.

While finding and keeping a job is key to avoiding recidivism, ensuring that individuals are not unnecessarily introduced into the criminal justice system in the first place is an even better tactic to promote public safety.

Students and future students also face counterproductive hurdles once they pay their fines or serve their sentence. For one, a marijuana conviction may trigger limitations on, or even bar access to, federal financial aid.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, individuals with a previous marijuana conviction may resume eligibility for federal financial aid if they complete a drug rehabilitation program, which includes passing two unannounced drug tests. An individual convicted of any marijuana offense faces a minimum one-year ineligibility period for receiving federal financial aid.

Because African Americans are disproportionately arrested, charged and convicted of marijuana offenses (and crimes in general), the collateral consequences outlined above fall disproportionately on them.

Forensic backlogs cause long delays

Alabama’s prohibition on marijuana possession has created a massive backlog in forensic tests – an often-overlooked problem that causes serious, unintended disruptions in the lives of people charged with a relatively minor offense while diverting resources from more serious crimes.

After someone is charged with a felony marijuana offense, the state must confirm whether the substance that was possessed, sold or shared was, in fact, marijuana. But during the first quarter of 2018, it took the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences (ADFS) an average of 278 days to process a drug case. At the end of that quarter, the ADFS had backlog of 30,684 drug cases awaiting analysis. The ADFS estimates that about a third of those are marijuana cases3

The ADFS processes evidence from more than 450 law enforcement agencies. In addition to testing drug samples, the agency analyzes biological evidence such as DNA from sexual assaults, homicides and other cases; runs a toxicology unit to test biological specimens; conducts forensic firearms examinations; and oversees the state’s breath-alcohol testing program.

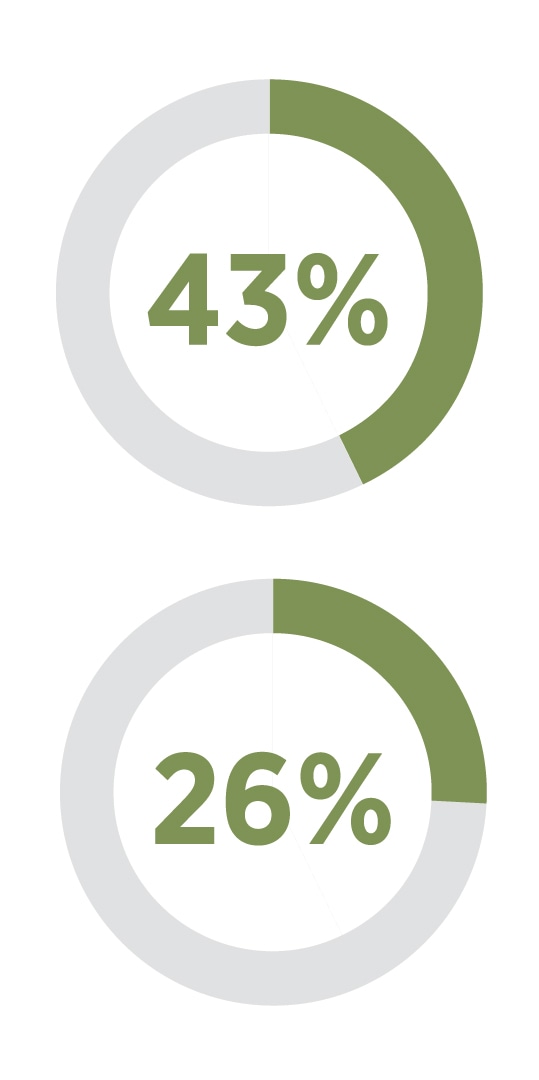

The agency, in other words, is busy – and it is very busy testing substances suspected of being marijuana. In 2017, marijuana cases comprised approximately 43 percent of cases processed by its Drug Chemistry Unit. The second most common substance sent for testing, methamphetamine, comprised 26 percent.

These backlogs have stunning real-world implications, not just for those awaiting trial on marijuana charges but for victims of violent crimes and for public safety as a whole.

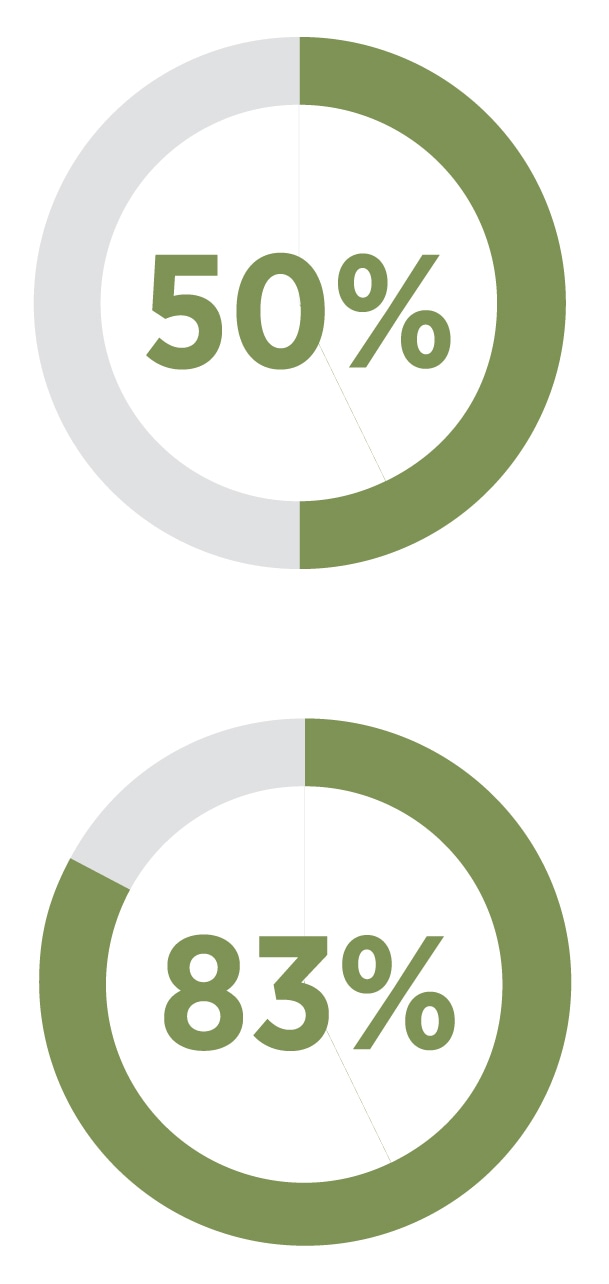

At the same time drug chemistry staff staggered under the burden of about 10,000 untested marijuana specimens, their colleagues in the Forensic Biology/DNA unit, which tests biological evidence, faced a backlog of 1,121 cases. About 50 percent of those were “crimes against persons,” including homicide, sexual assault, assault and robbery. While the Drug Chemistry and Forensic Biology/DNA units may be separate, they do not operate in a vacuum. Resources used by the Drug Chemistry unit to test marijuana divert resources from the Forensic Biology/DNA unit, slowing down investigations related to serious crimes.4

As they await results, people facing marijuana charges are subject to a variety of consequences, such as being required to check the box on most job applications saying there is a pending criminal charge against them or being pressured by police to “flip” on anyone else they know who is involved in drug activity in any way – even low-level users – in order to obtain a favorable plea deal.

In the worst cases, people who cannot afford to bond out of jail and are ineligible to be released on their own recognizance may find themselves confined for months or longer as prosecutors await test results. This means jobs lost, children separated from their parents and communities ripped apart – before anyone has even been convicted.

In a letter responding to written questions, ADFS Director Della Manna noted that 10 years ago, the Drug Chemistry unit had no cases backlogged for over 90 days. A 2009 budget cut sliced the agency’s budget nearly in half, from $14.3 million to $8.5 million, forcing a hiring freeze and the closure of three laboratories. (During fiscal year 2019, the budget will increase to $11.6, still well below the 2009 high.)

Sentencing enhancements only worsen penalties. Read our special section on these failed remnants of the War on Drugs.

Pretrial purgatory

These backlogs are the predictable result of Alabama’s decision to impose and attempt to enforce a needlessly harsh statutory regime without providing the resources necessary to ensure the information required to determine whether a crime has even been committed is processed promptly and efficiently.

Because of the state’s insistence on policing marijuana, evidence pertaining to homicides, sexual assaults, assaults and other violent attacks languishes in ADFS backlogs, while individuals accused of marijuana-related offenses languish in pretrial purgatory with devastating real-world consequences.

In June 2014, Montgomery County faced a backlog of 1,200 drug cases and an average 15-month wait time for test results. Rather than drop charges, de-prioritize enforcement of marijuana laws or take any other step to remedy the structural issues that created the backlog, District Attorney Daryl Bailey established a special docket “to see if any of these defendants will go ahead and plead guilty to these charges without the scientific results,” Bailey told WSFA News.

Without citing any evidence, Bailey said the backlog was creating a public safety crisis, with drug users “breaking into your car or your house to feed their drug habit and the criminal justice system has done nothing to deal with the problem because of this backlog.”

Bailey added, “Our research tells us most of these defendants will go ahead and plead guilty to these charges because they want to get the help that they need and they want to get this over with and go on with their lives.” He planned to speed through 1,000 cases in a single month, despite the fact that he would be moving forward on criminal cases in which he had no way of knowing, let alone proving, that the various substances in question were illegal drugs.

According to Virgil Ford, a Montgomery County defense attorney who handled many of the cases assigned to this special docket, defense lawyers were concerned about the constitutional implications of Bailey’s plan, because pleading guilty “on information” – that is, without an indictment – requires defendants to waive certain rights and opportunities to challenge the cases against them. Though the special docket may have been beneficial for certain people – such as those who readily and willingly acknowledged they were guilty but were offered plea deals that transformed potential felonies into misdemeanors – some defendants who were in jail because they could not afford to post bond were in a terrible position. For them, it meant a choice between sitting in jail or pleading guilty, even if they were innocent.

“Desperate people do desperate things,” Ford said in an interview for this report. “It’s the incarcerated individuals, indigent, and maybe mentally challenged – those are the ones that you really have to pump brakes on, and it’s an ethical dilemma for the defense attorney. Do I plea this guy? And even now I’m skittish about it.”

Ultimately, due to the insistence of defendants who were out on bond to face trial rather than plead out, Montgomery’s 2014 special docket “kind of went away,” Ford said.

The backlog worsened. By June 2016, Montgomery’s drug-related backlog stretched to 1,604 cases; defendants in drug cases waited more than two years for a trial while ADFS processed the evidence. That time, instead of establishing a special docket, prosecutors and judges urged defense attorneys to place eligible clients in drug court, a one-year program involving classes, community services, random drug tests and a $209 monthly fee (or $2,508 a year). That’s more than 16 percent of a full-time minimum wage worker’s gross annual income.

People who successfully complete drug court have their records cleared, but those who fail or drop out are left with felony convictions. According to Ford, the program is “grueling,” with too many costs, sanctions and requirements to make it doable for all but the most committed and well-resourced participants. As a result, many fail out or drop out. And for those unable to afford the monthly fees, drug court may not even be an option in the first place.

For people who cannot afford drug court or even to make bond, being arrested for possession of even a small amount of marijuana puts their life on hold. Like Montgomery County’s special docket, the effort to manage the backlog by offering drug court reinforced a two-tiered system of justice, where people with money can purchase a clean record, while people without money cannot.

Police made 2,351 arrests for marijuana possession in 2016, the last year for which data was available. They arrested thousands more for having the intent to purchase the drug or for drug paraphernalia.

Each arrest represents a negative interaction with law enforcement and can trigger the beginning of a lifetime of consequences. It means a life put on hold, at best, and derailed completely at worst – all for doing what is perfectly legal in states inhabited by 70 million other Americans.

A breakdown of all marijuana-related arrests, including for production and trafficking, reveals the real story of marijuana prohibition in Alabama isn’t about cartels and kingpins. Rather, it’s about needlessly entangling ordinary, otherwise law-abiding people in Alabama’s criminal justice system.

In fact, the overwhelming majority of people arrested for marijuana offenses in Alabama between 2012 and 2016 – 89 percent – were arrested for possession. (See Fig. 1) In 2016, possession arrests were 92 percent of all marijuana offenses.

While the number of simple possession arrests declined between 2013 and 2016, police continued to arrest far more people for marijuana possession than for robbery. Police made 1,314 arrests in 2016 for robbery; that’s despite the fact that there were 4,557 reported robberies that year.

Marijuana possession also stands out prominently from other offense categories because of the significant racial disparity among those arrested.

In 2016, black people in Alabama were more than four times as likely as white people to be arrested for possession – despite ample evidence that black and white people use marijuana at similar rates. (See Fig. 2) As an offense category, marijuana possession had the largest racial disparity among the 20 offense categories with the most arrestees.

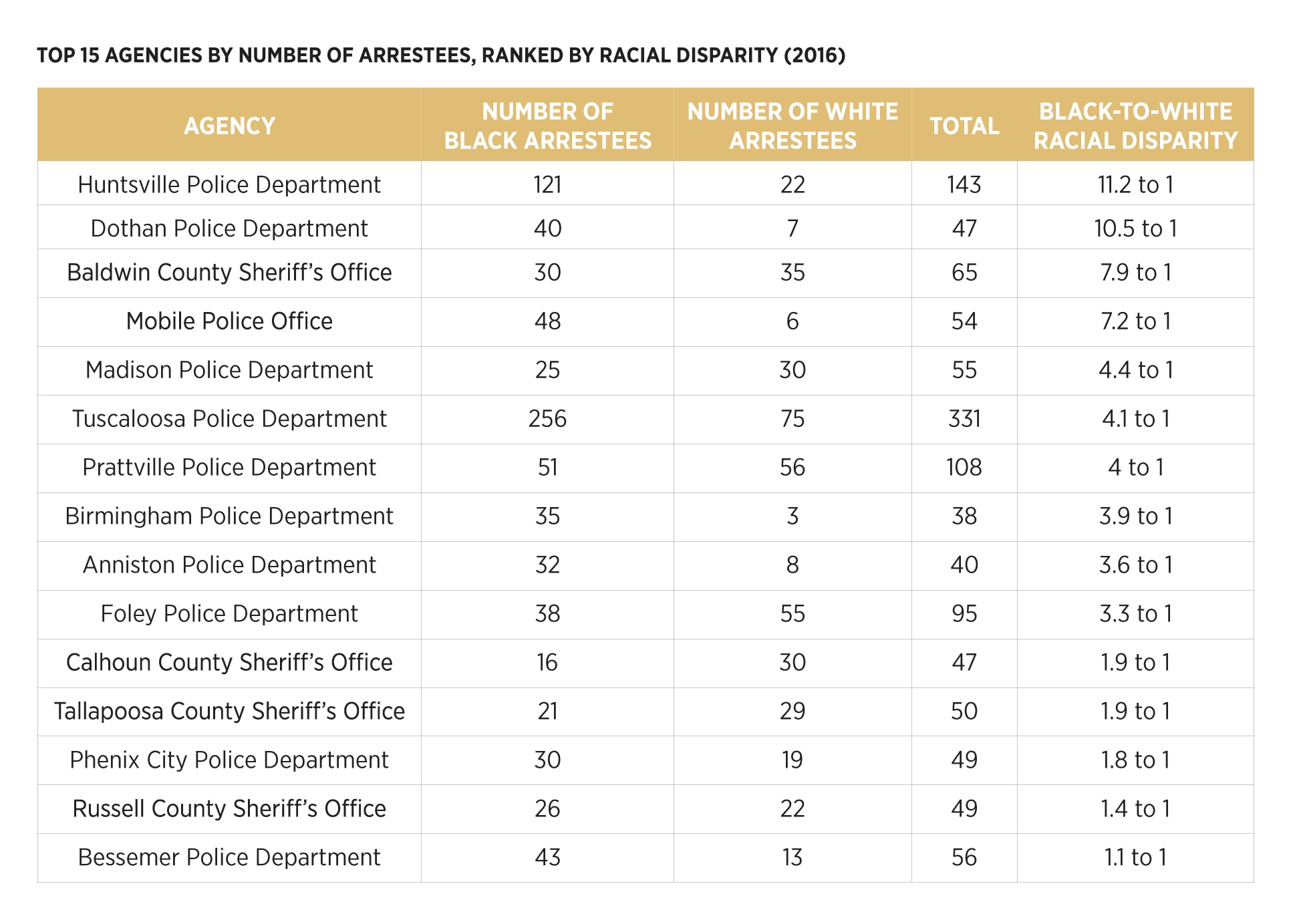

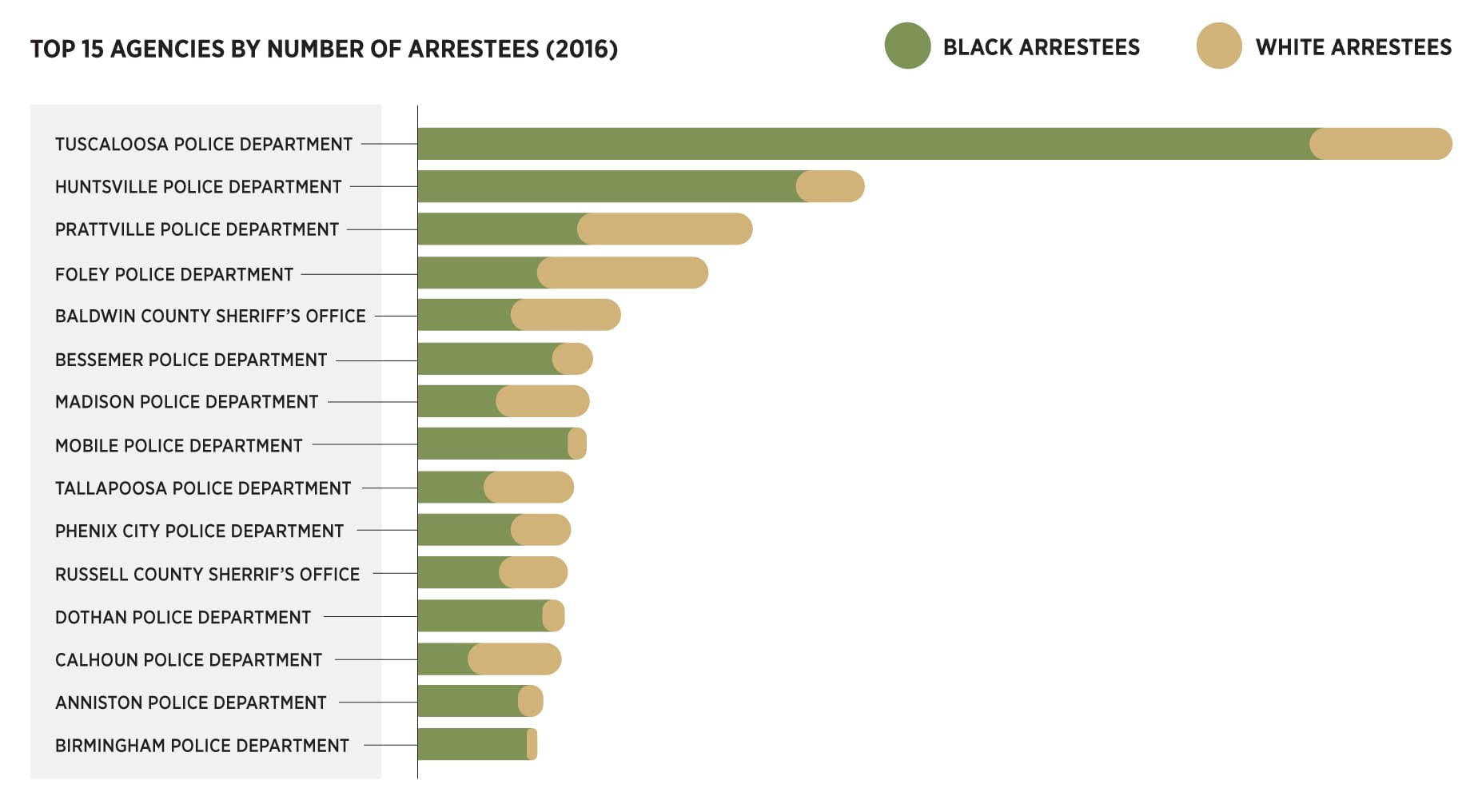

For the year examined in this report, 2016, the racial disparities in some law enforcement jurisdictions far exceeded the average disparity across the entire state. Among the 50 law enforcement agencies that arrested the most people for possession, the disparities exceeded 10-to-1 in seven jurisdictions: Huntsville, Dothan, Gulf Shores, Pelham, Troy, Etowah County and Decatur.

> 1,410 black people were arrested for marijuana possession in 2016. 877 white people were arrested. View the map.

Police in the top 15 agencies arrested 1,227 people for marijuana possession – more than half of all people arrested for the offense in 2016. In 10 of these jurisdictions, black residents were more than twice as likely to be arrested for possession as their white neighbors. More than 1 million Alabamians live in those 10 areas.

The data also show a greater racial disparity among felony possession arrests statewide. Police arrested black people for felony possession five times more often than white people. (See Figures 5) By comparison, they were three times more likely than white people to be arrested for misdemeanor possession. This is alarming, considering the wide latitude Alabama law enforcement officers have to declare whether a first possession offense meets the definition of a felony rather than a misdemeanor.

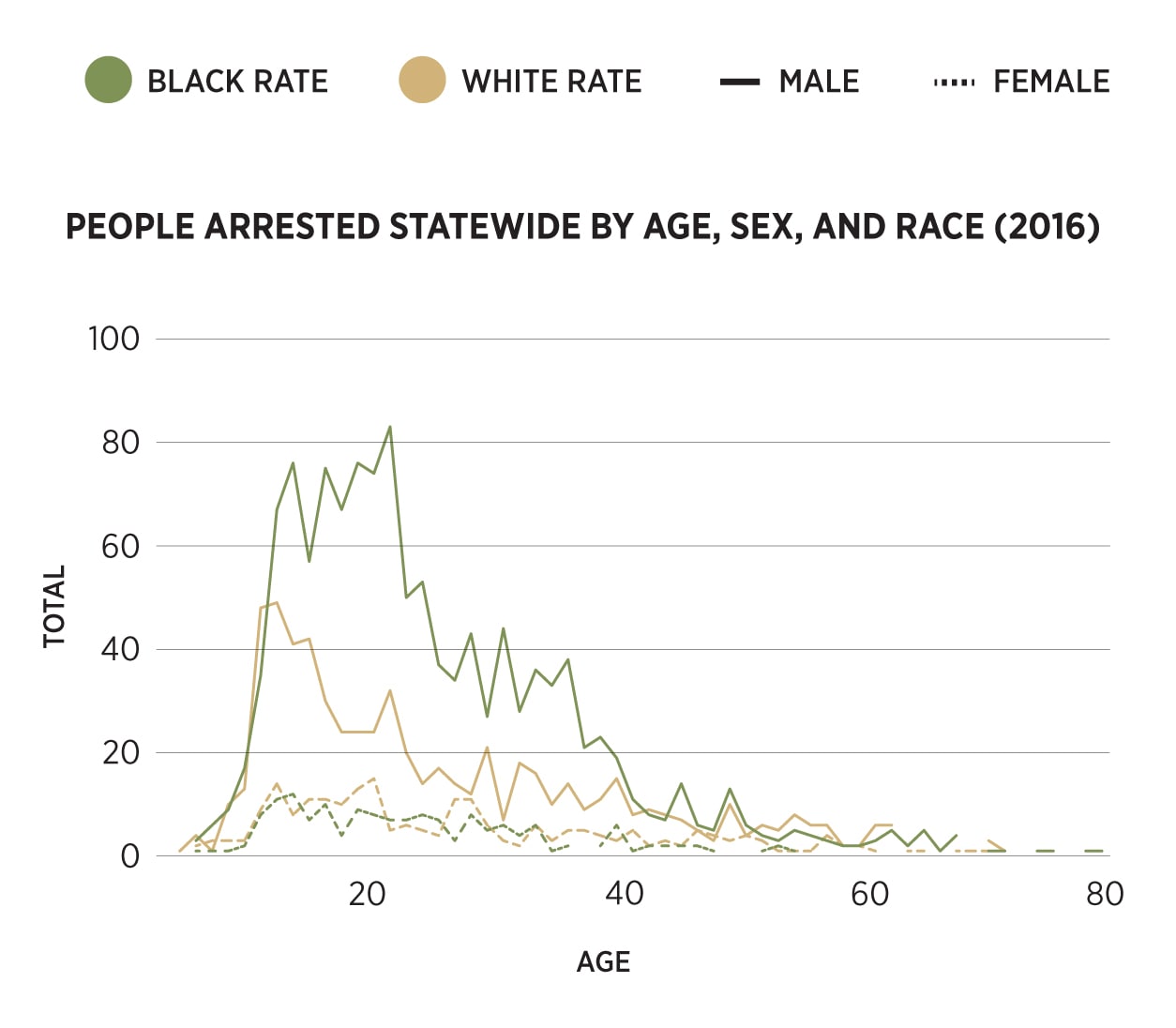

The greatest impact of this disproportionality falls on young black men, who are often arrested for possession in their 20s. A plurality of people arrested for marijuana possession in 2016 in Alabama (26 percent) were between ages 20 and 24, thus providing an early, unnecessary and damaging introduction to the criminal justice system.

Overall, 83 percent of people arrested for marijuana possession were men. The numbers of white men and black men arrested in 2016 diverged dramatically at age 20 and did not converge again until age 40. (See Fig. 7) This divergence appears to have driven, at least in part, the magnitude of the overall racial disparity in marijuana arrests. Such disparities peak among those arrestees aged 25 to 29. Black people in that age group were five times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than their white peers.

Police in Alabama also arrested 128 people for marijuana distribution/sale in 2016. Of those, 79 were black and 49 were white. More than half – 54 percent – were in their 20s. The statewide racial disparity among those arrested for distribution was similar to the disparity among possession arrestees. Black people were 4.2 times more likely to be arrested for distribution/sale than white people in Alabama. (See Fig. 8)

In short, the data reviewed for this study reveals that Alabama’s prohibition on marijuana possession affected thousands of people in 2016. And it’s utterly clear: Alabama law enforcement investigations disproportionately target young black men.

Millions of people smoke marijuana in America. And for the vast majority, the only real harm comes if they are arrested.

If that happens, the consequences can be life-altering – especially in Alabama, which has yet to relax its harsh laws even as many other states have reformed theirs.

In Alabama, a marijuana arrest can mean the end of a promising college career – or the loss of a job.

It can mean less food on the table or no new school clothes for the child of a single parent.

It can mean years of paying off court debt, or the loss of student loans or other government benefits.

It can mean jail time and even hard time in prison.

And, it can mean the loss of trust in law enforcement – particularly for black communities, which face disproportionate enforcement.

The human toll of marijuana prohibition is, in fact, incalculable. But it’s devastating to thousands of people – often exacting a cost on children and other family members as well. At the same time, there can be little doubt that it’s a drain on Alabama’s economy.

Alabama residents are right to ask: Why? To what end?

Here are the stories of just a few people who have been drawn into Alabama’s criminal justice system because of marijuana.

County spends $21,000 to jail man over $10 worth of marijuana

Wesley Shelton was caught in late 2016 with a small bag of marijuana he bought for $10.

What followed was a Kafkaesque episode that illustrates the absurdity and wastefulness of marijuana enforcement in Alabama.

Shelton would spend the next 15 months in the county jail awaiting adjudication.

And while he may have gotten a rotten deal, so did the taxpayers of Montgomery County. The county likely spent at least $21,000 to keep him locked up.5

It began when Shelton, 56, dozed off on a bench. A police officer came along and asked to search him. The officer found the marijuana and hauled him off to jail. Even though the amount was small, the state charged him with a felony because of a prior possession conviction.

Weeks later, he had a preliminary hearing before a local district judge, who determined that there was probable cause for the arrest and bound the case over to the grand jury.

That’s when several failings of the criminal justice system began to conspire against Shelton. First, the court refused to release him without bail because he didn’t have a stable home address. Then, his bail was set at $2,500. Shelton couldn’t come up with the $250 he needed to post bond.

Finally, the prosecutors faced a hurdle of their own making before they could proceed.

The district attorney in Montgomery County does not seek to indict people until he gets a report from the drug lab, according to Brock Boone, an ACLU attorney and former Montgomery County public defender.

Thanks to a huge backlog of cases, it can take the underfunded Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences (DFS) months to complete a test.

So, Shelton stayed in jail.

“This is very common in Montgomery,” Boone said. “There are other Wesley Sheltons in the Montgomery County Jail right now.”

Shelton languished in jail as his relationships frayed and sense of purpose diminished.

He estimates he wrote more than a dozen letters – to his attorney, to the court clerk and to the district judge, each time begging to plead guilty and go home.

In a Sept. 27, 2017, letter, he wrote, “I’m [sic] admit my guilt. I was in possession of marijuana. I’ve written 5 time [sic] asking for a bond reduction. I’ve received not one answer, from the court. … I’ve never in my life feel [sic] so totally helpless, with no end. Help me please.”6 Several weeks later, he wrote again: “I admit my guilt. I’ve been in jail for 13 months and counting. I have very few options. I need some help!”7

No one seemed to notice. Shelton was caught in a kind of purgatory between the district court, which had finished with his case, and the circuit court, which wouldn’t pick it up until there was an indictment.

In December 2017, Shelton’s pleas finally got through to someone. He pleaded guilty to first-degree possession – a felony. The state never got around to testing his marijuana.

After his plea, Shelton was freed. But he had lost more than a year of his life for $10 worth of marijuana.

“Right now, in my life, because of that 15 months, I feel as though I’m 10 years behind where I’m supposed to be,” he said.

Grandmother overwhelmed by collateral consequences

A conviction for a marijuana offense in Alabama can cause massive collateral damage to a person’s life. That’s especially true when a person is an elderly cancer patient.

Mary Thomas, 75, never smoked marijuana heavily, but she did enjoy it recreationally with her family and friends from time to time. She had an open-door policy at her home in Northport. Occasionally, she let family friends who were down on their luck stay with her. In 2011, a friend of her grandson came to stay at her house. They shared meals and he helped in the garden.

Thomas liked the man – until the day police showed up.

It turned out he was a confidential informant. To keep himself out of trouble, the man tracked and reported unlawful activity to police. One day, police officers let themselves in through Thomas’ unlocked door. They handcuffed her and took her to jail.

Thomas had recently been paid, and police, using Alabama’s notoriously abusive civil asset forfeiture program took and kept over $300 in cash from her wallet and about $50 from the pocket of a housecoat. They claimed the money was evidence of drug dealing.

According to Thomas, she had a small bag of marijuana when police turned up. Even so, police charged her with possession for “other than personal use,” a felony. She paid $1,800 for bond and another $5,000 to a lawyer who advised her to plead guilty in exchange for probation. Thomas, who had never been in serious trouble before, was terrified of going to jail. She took the plea. Her lawyer never advised her to challenge the forfeiture of her paycheck money, and the state kept it.

She never saw her houseguest again.

Thomas’ life spiraled out of control. She was on probation for about a year. She was on the hook for about $2,000 worth of court fines and fees. The state took the money from her income tax refund until her court debt was settled. With costs piling up, she needed to keep working. But because her driver’s license was suspended as an automatic consequence of her conviction, she had to find people to drive her to and from work each day – no easy feat, since she worked the midnight-to-8 a.m. shift at a halfway house.

Worst of all, from Thomas’ perspective, she lost her right to vote. “From the day they said black folks could vote, I been voting,” Thomas said. “That was one of my rights, and it was taken from me.”8

Making matters far worse, she developed breast cancer. She lost 70 pounds. In response to the stress and depression, she began drinking heavily, and in 2013, two years after her felony conviction, she was arrested for public intoxication. A judge showed leniency after she removed her hat – as was required by court rules – and he saw that she was bald, a permanent consequence of her cancer treatment.

One day, her niece brought her some marijuana and insisted that she smoke it. It helped with her appetite and pain.

Today, Thomas, is in relatively good health and living in Tuscaloosa, where she cares for her 55-year-old adult son with special needs. She no longer abuses alcohol. She has forgiven the man who turned her in to police, she said.

Bad luck, a load of court debt and a broken dream

Kiasha Hughes picked the wrong place to change for work.

Rushing to make it from the laundromat to her shift as a University of Alabama food service worker, she and her boyfriend parked behind a fast-food joint so she could change into a freshly laundered uniform. Responding to a call about suspicious activity, police officers pulled up and searched the car.9

Seeing the approaching police vehicle, her boyfriend had asked her to hide a few baggies of marijuana in her clothes. Now they were both going to jail.

Hughes, then 23, was two months pregnant and in the throes of pregnancy-induced nausea. She waited for hours in a vomit-spattered holding area before police photographed, fingerprinted and booked her. By the time she was “dressed in” to jail, dinner had already been served. She spent a miserable few hours trying to rest on a mat in a crowded dorm before bonding out around midnight on Valentine’s Day 2014. By the time the ordeal was over, she was so sick and dehydrated that she had to be given intravenous fluid at a hospital.

Hughes, who says she doesn’t even like marijuana, said it was the first and only time she was ever arrested. But because police judged that the marijuana was for “other than personal use” – a subjective determination based on officers’ suspicion alone – and because they also found paraphernalia in her boyfriend’s car, she was charged with a felony.

She had just cashed her paycheck, and police, using Alabama’s abusive civil asset forfeiture program, took that money from her wallet when they arrested her, claiming in court that it was the proceeds of drug activity. Exhausted and sick from a difficult pregnancy, she was too stressed to challenge the $547 seizure in court – an effort that would in all likelihood have cost her more in attorney’s fees than the money was worth.

And she had bigger things to worry about. Having dreamed her whole life of working in health care, Hughes found herself suddenly ineligible for the positions she interviewed for at area providers. “They don’t hire pending felonies. And then that made me very upset, cause I’m thinking I’m fixing to get the job and they call me back, ‘Well we can’t offer you employment because of your background.’”

Hughes had been studying to be a medical assistant when she got pregnant with her daughter Jameria, now 3, and was seeking a job that would burnish her resume. Instead, she found herself working the overnight shift at a poultry processing plant, deboning chicken for $12 an hour. She’s grateful for the job, which provides insurance and other benefits, but sad and frustrated that her arrest cost her the opportunity to advance her career goals and better provide for her children.

It took two and a half years for Hughes’ case to finally get resolved.

At first, law enforcement tried to get her to share incriminating information about people she knew, but Hughes had nothing to tell. In 2017, she was offered an opportunity to participate in a diversion program that might have resulted in a clean record. But, pregnant with her second child and still working a third-shift job so she could look after her little girl during the day, she realized she would never be able to meet the program’s demands or pay the $1,000 needed to enroll, plus court costs and the costs of drug screenings. (Tuscaloosa does waive diversion fees on a case-by-case basis, but the determination that an individual qualifies is made only after they enter a conditional plea of guilty and register for the program.)

“You have to take classes, you would have to pay for drug testing” and do community service, Hughes said. “And I knew I wasn’t gonna be able to wake up and do that.” Instead, two and a half years after her arrest, she took a deal and pleaded guilty to misdemeanor possession of marijuana. She received a year of probation, and a bill for $1,440 in court costs.

Each month, Hughes pays $40 to a probation officer and $50 toward her court costs – money she can ill afford. The overnight child-care center where her children stay while she works the third-shift is

expensive, and she plans to take a second job on weekends. Working multiple jobs will make it even harder for her to return to school and get her derailed medical career back on track.

Even so, asked where she hopes to be in five years, Hughes, now 27, said, “I’ll be graduated and probably working, and working on another degree. Because I don’t want to stop. I want to keep going. I want to progress into a nurse.”

Family traumatized, young man's life ruined – for a few grams of marijuana

Sabrina Mass sat on her living room couch, her arms twisted behind her by handcuffs. Her thin bathrobe gaped open in front, leaving her breasts exposed to the police who had knocked down the door. Her son Michael Brooks, 24, lay on the floor with an officer’s gun to his head. Her daughter and tiny granddaughters, ages 1 and 3, emerged from a bedroom, only to be driven back at gunpoint by the officers who were searching the house.

She had seen the news about unarmed black men just like her son being killed by law enforcement officers.

Mass prayed the police would not shoot Michael.

“I started having these visions, like they’re gonna kill my son.”

The officers – who, according to Mass, said they decided to come in with guns drawn after seeing military decals on the cars outside (Brooks was a member of the National Guard) – didn’t shoot Brooks. Instead, after finding a few grams of marijuana in a bedroom, they took him and his girlfriend to the station.

An investigator with the Mobile City Police’s Narcotics and Vice Unit told Brooks he had confidential informants who would testify that Brooks had sold them marijuana. Everything would be fine, the officer told him, if Brooks would be a confidential informant – and as long as he told no one and promised not to call a lawyer.

Mass, a retired nurse who now works as a security guard, knew something was wrong when her son came back from the police station so stressed that he was throwing up. After growing up in a Texas orphanage, she was as protective of her children as she was strict with them. When she pried the story out of her son, she immediately found a criminal defense lawyer, Chase Dearman.

Dearman spoke with police, and Brooks believed his troubles were over. But a few weeks later, he started getting texts from the police officer asking when he would provide information about drug deals.

Brooks ignored them.

He got a job offshore working in the oil and gas industry out of Houston.

In late December 2015, while Brooks was working, Mobile police executed another raid on Mass’ house, using the same warrant they used the previous July. Though Brooks wasn’t even living there the first time, they returned before dawn twice more to turn the house upside down looking for him.

Mass called Brooks, and he turned himself in as soon as he was able to get back to Alabama. But he couldn’t fathom why they were after him.

A former honor student and football player for Mobile’s W.P. Davidson High School, he had attended college for three semesters before returning home to support a son he was expecting. He joined the National Guard and took a job in a restaurant, earning enough to live independently. He did not sell marijuana.

Indeed, Brooks’ case file shows that police were not even interested in him when they began their investigation. Rather, they were focused on his girlfriend. Because she sometimes stayed over with Brooks at Mass’ home, they started sending an informant there regularly to attempt to incriminate both of them.

The search affidavit indicates that the girlfriend, in July 2015, sold the informant four grams of marijuana, and a narrative written by the officer who arrested Brooks says he confessed to occasionally distributing marijuana. At a different point, according to attorney Dearman, the officer alleged that the girlfriend got the marijuana she sold to the informant from Brooks. Under the same Alabama law that makes passing a friend a marijuana cigarette at a concert “distribution of marijuana,”10 that act would make Brooks a felon.

Brooks says he never distributed marijuana to anyone and never told the officer that he did.

The charges hung over his head for years.

He lost his oil job when the state repeatedly moved his court date, forcing him to delay returning to the long stints offshore. He was honorably discharged from the National Guard. He obtained a commercial driver’s license in 2017, but no one wanted to hire a young black man with a pending felony charge.

At 26, after years of living on his own and paying his own way, he ran out of money and moved back in with his parents. “Offshore, I was averaging $55,000 a year – to nothing,” he said.

Finally, in February 2018, Brooks could stand it no longer. When the state offered him a chance to plead guilty to possession of paraphernalia – a violation for which he would serve informal probation for one year – he took it. Soon after, he secured a job driving trucks for Amazon. But the case “set me back years,” he said.

“All my bank accounts are closed. I’m used to working and making money. My credit’s messed up. I had to do this just so I could continue my life. I’m trying to get back to where I was.”

The whole family is scarred by the experience. Mass’ granddaughter, who was 3 when police first burst in that day, is now 6. She is so traumatized by the incident that she cannot bear to see Mass dressed for work as an armed security guard. She is currently in counseling.

And Mass, who used to love seeing police in her neighborhood because they made her feel safe, and who once stood with a former Mobile police chief to testify in favor of a teen curfew within city limits, doesn’t know what to think.

“The kids go through the baby phase, elementary, middle school, high school, as a minority family, and they beat the odds,” Mass said. “They beat the odds! And then, this.”

“We’re actually paying the police to come violate families,” she said. “We’re paying you to come violate our house and our home and our families. Our money, out of our hard-working sweat. Now how stupid does that sound?”

Fifteen officers, pistols drawn, swarm student’s dorm room

More than a dozen police officers burst into Nick Gibson’s dorm room early one morning in 2013. Before long, he and 60 other students would be arrested in the largest drug raid on or near the University of Alabama grounds in at least 30 years.

Many of the students were caught doing something that today is legal in nine states: possessing small amounts of marijuana. But in this case, that activity was the pretext for a massive pre-dawn drug raid still remembered for the students’ lives it altered.

As the police swarmed his room, “All I see is flashlights and gun barrels,” Gibson, now 24, recalled. The police pulled him out of bed and onto his hands and knees. “They start tearing my room apart.”

The officers had a warrant and quickly found a bag of marijuana. Gibson claimed the drugs immediately. “That’s my weed. I was smoking it,” he recalled telling the officers. The officers also, using Alabama’s easily abused civil asset forfeiture rules, took $1,250 of Gibson’s money, which he said was from his mother, and dumped out a jar of one-dollar bills he had been collecting.

Gibson said he counted 15 officers, some with pistols drawn and all wearing gear like the SWAT teams he had seen on TV.

The officers escorted Gibson out of the dorm, in handcuffs, into a van with more than a dozen other students from the building. Two were Gibson’s roommates.

Gibson later found out the van was one of many filled with students. The large-scale operation was carried out by the multi-agency West Alabama Narcotics Task Force. The agents had been allowed by the UA administration to carry out the raids. At the jail, Gibson watched throughout the day as 74 more arrestees arrived, 61 of them students. Though there were a handful of other drug charges, most dealt with sale or possession of marijuana. Of the 183 drug charges that day, 75 were for first-degree possession of marijuana, a felony and the charge subject to a prosecutor’s discretion in Alabama.

Gibson fell in that category. In fact, he rarely sold and only sometimes possessed marijuana, he said. Sometimes, for example, he would give a friend a little bit of marijuana in return for an order of Buffalo wings the next time the two got together.

After the February arrest, Gibson was accepted into a diversion program for students. But he was in trouble again that November. The task force again caught him with marijuana. This time, the felony charge stuck.

Today, Gibson lives in Tuscaloosa and works at a restaurant. He did not graduate. The 2013 ordeal cost his family more than $40,000, he said, in court fees and legal costs.

Not all universities in Alabama see such strict marijuana enforcement as a positive thing. In an article about the 2013 raids at UA, the dean of students at Birmingham-Southern College, Ben Newhouse, said things would be handled differently there. In one three-year period, there were 87 drug violations reported on the Birmingham-Southern campus, but no one was arrested. “Philosophically for a first-time marijuana offense ... we try to treat that as educationally as possible,” Newhouse said.

Federal law still prohibits the use of recreational marijuana. But since 2012, a movement to legalize or decriminalize marijuana to varying degrees has taken hold in nearly every U.S. region

More than one-fifth of the U.S. population – about 70 million people – now lives in a state or territory that allows adults to use marijuana recreationally. Another 41 percent of Americans live where a person can legally obtain marijuana for medical purposes. The remaining 38 percent live in states that haven’t legalized marijuana but are likely to have decriminalized it to some degree.

As the early evidence shows, the benefits of full legalization could prove enormous. Not only would legalization shave billions in costs from the criminal justice system, it holds the promise of an economic bonanza.

A recent study by the data analytics firm New Frontier Data estimates that nationwide legalization would generate 1.1 million new jobs by 2025 and at least $132 billion in tax revenue over the next

decade. Three of the states where marijuana has been legal the longest – Colorado, Washington and Oregon – already have collected a total of $1.3 billion in taxes.

Nine states and the District of Columbia now allow the legal sale and possession of marijuana for recreational use. Washington and Colorado ended prohibition in 2012. They were followed by Alaska (2015), the District of Columbia (2015), Oregon (2015), Nevada (2017), California (2018), Maine (2018), Massachusetts (2018) and Vermont (2018).

The sky has not fallen in those states. Quite the contrary.

Studies strongly suggest the impact has been decidedly positive. Recent reports show that drunken-driving arrests are down, new tax revenues are funding education, the rate of marijuana use among adults and youth is stable, and concerns about increased crime haven’t been borne out. Where challenges have arisen, so have thoughtful solutions.

Crucially, arrests for marijuana offenses – and the corresponding human and fiscal costs – have fallen dramatically.

Marijuana Arrests Virtually Eliminated

The decrease in arrests is perhaps the most important goal and benefit of legalization. As this report shows, an arrest for marijuana can dramatically and unfairly alter a person’s life. The fiscal costs to taxpayers and the collateral costs to individuals are enormous.

The research shows legalization is – as intended – lowering arrest rates for possession and distribution in these states. Thousands of people are being spared the stigma, economic stress, and unreasonable consequences of an arrest for a marijuana offense like simple possession.

“Arrests … have plummeted since voters legalized the adult use of marijuana, saving those jurisdictions hundreds of millions of dollars and preventing the criminalization of thousands of people,” says a recent report by the Drug Policy Alliance.

Oregon experienced the most dramatic reduction. In 2016, police made 6,741 fewer marijuana arrests than in 2015 (the year before legalization) – a 96 percent reduction, according to the Drug Policy Alliance report. Washington, too, showed a big change. The state posted a 98 percent drop in marijuana arrests between 2011 and 2015 – from 6,879 to just 120. A similar percentage drop in Alabama would equate to approximately $22 million in reduced expenditures.

Colorado

In Colorado, the number of marijuana arrests fell nearly 50 percent – from 12,894 in 2012, the year the state passed its legalization amendment, to 6,502 a year later. A small increase – 7 percent – followed in 2013, but overall the number of arrests remained significantly lower. By 2015, there was more progress. “The total number of marijuana-related court filings in Colorado declined by 81 percent between 2012 and 2015 (10,340 to 1,954), and possession charges dropped 88 percent (9,130 to 1,068),” the Drug Policy Alliance report says.

Though hardly true for the state as a whole, racial disparities in arrests for the remaining marijuana offenses fell in six counties where they had previously been particularly egregious. In one such county, Arapahoe, police arrested black people for marijuana offenses 3.9 times more often than white people in 2010 and 2.5 times more often by 2014. Reclassifying marijuana might be an important step toward reducing such disparities, but it may require broader policing reform to prevent new disparities from arising.

Washington, D.C.

Similarly, Washington, D.C., saw a dramatic drop in the number of marijuana arrests after it reclassified the drug in 2014 and legalized it in 2015. The number of arrests fell by 83 percent from 2014 to 2015, according to the Drug Policy Alliance.

In 2016, just 35 people were arrested in D.C. for possession. But there, too, the number of public consumption arrests rose, and racial disparities persisted. The Drug Policy Alliance called the results of D.C.’s policies “mixed” with regard to arrests.

Indeed, with the public consumption statutes, the District replaced an old prohibition on marijuana use with a new one. Consuming marijuana in public became a criminal misdemeanor on July 17, 2014; reclassification of possession took effect that same month. Over the next year and a half, police in the District racked up 259 arrests for public consumption, according to the Drug Policy Alliance. The next year, 2016, brought a 182 percent increase in the number of public consumption arrests (661).

Police heavily enforced the new public consumption ban on black people, especially black men, and lightly on white people. The Drug Policy Alliance found that a black person in D.C. was 11 times more likely than a white person to be arrested for public consumption.“This is despite the fact that black residents only make up around 49 percent of D.C.’s population, and use marijuana at similar rates to white residents,” the report says. Distribution arrests, which had fallen from 2014 to 2015, also rose again in 2016. The distribution ban, too, was heavily enforced on the black community.

Still, the sharp drop in the number of possession arrests means that 2,125 fewer people were arrested for possession, distribution/sale and possession with intent to distribute/sell in 2016 compared to 2014.

Even with the new ban on public consumption, 1,723 fewer people overall were criminalized for marijuana in 2016 compared to 2014.

That isn’t to say D.C.’s Metropolitan Police Department has taken to a lighter touch when enforcing drug policy at large. The department’s enforcement of other drug prohibitions actually led to a rise in all narcotics arrests – from 2,025 in 2015 to 3,184 in 2016, a 57 percent increase. In fact, the department established a new unit within its narcotics division, the Narcotics Enforcement Unit, “to transition from targeting low-level drug users to focus efforts on narcotics suppliers who distributed drugs in D.C.” The new unit racked up 1,250 arrests in 2016 alone.

The research, especially into data from Washington, D.C., and Colorado, shows that marijuana legalization is unlikely to eradicate policing practices that lead certain communities to lose faith in law enforcement. However, it shows that legalization does, as a core feature, rearrange law enforcement priorities. In places that have legalized marijuana, police are simply no longer locking up as many people for partaking in relatively safe drug use in private.

New Orleans

Short of full legalization, reforms at the city level can have a significant effect on the number of marijuana arrests. A 2016 law in Louisiana placed the handling of marijuana offenses under municipal purview, permitting cities to decriminalize the drug.

New Orleans took advantage of the new law. The city council quickly created a new fine schedule for marijuana possession: $40 for first-time offenders, $60 for second-time offenders, $80 for third-time offenders and $100 for four or more offenses. New police department policy then “made arrests the exception rather than the rule,” wrote The Times-Picayune.

Legal Marijuana Fills State Coffers

As arrests declined, revenues from the taxation of legal marijuana soared. Taxes on sales have “reaped unexpectedly large benefits,” researchers reported in 2015.

Colorado, Oregon and Washington have imposed a combination of excise, sales, and local taxes and licensing fees on legal marijuana, according the Cato Institute, a free market think tank.

Colorado reaped more in the year after legalization than advocates had anticipated. In 2015, the state collected $135 million from the marijuana industry. And that was just the beginning. By the end of 2017, the state had raised $600 million and disbursed $230 million to the Colorado Department of Education.

Oregon levied its first tax on legal marijuana in 2016. Forty percent of the revenue goes to the state’s education fund, according to the Drug Policy Alliance. Since legalization, Oregon has raised $34 million for its schools.

Similarly, in Washington, marijuana sales tax revenue topped $70 million in the first year after legalization – double the amount that was expected. The state spends a quarter of the funds on substance abuse treatment services and 55 percent for health care.

The Drug Policy Alliance also reports that Nevada, which legalized marijuana in 2017, expects to raise $56 million between 2018 and 2020 for the state’s education system. And while revenue projections might be too preliminary in California, where legalization took effect at the beginning of 2018, the state plans to fund youth drug use prevention initiatives and environmental restoration. Ultimately, up to $50 million will go to fund a community reinvestment grant program.

Vermont

Rand Corporation researchers noted that marijuana revenues depend on lots of factors, not least the actions of surrounding states: “If Vermont legalizes with high taxes and neighboring states legalize but assess low taxes, people in Vermont could cross state lines to purchase, just as cigarette smokers now do in places with high tobacco taxes. Conversely, if Vermont is the first state in the Northeast that legalizes, then, until other states follow, Vermont could generate considerable revenue from sales to residents of other states.”

Unlike the West Coast, the East Coast does not have a cluster of states in which marijuana is fully legal. Rand researchers attempted to quantify the potential revenues by looking at how many marijuana users live in adjacent or nearby states. They found that within 100 miles of the state’s borders there are more than 17 times as many marijuana users as there are in Vermont. The area included Boston and Providence, along with rural areas of Maine and New York. “Marijuana tourism” in Vermont from such areas “is likely to be very attractive to a legal marijuana industry and perhaps to a cash-strapped state government,” researchers noted.

This report does not attempt to make a similar estimation for Alabama. However, it should be noted that the South has legalized marijuana to an even lesser degree than the Northeast. Large segments of the populations of three major cities – New Orleans, Nashville and Atlanta – lie within 150 miles of Alabama’s borders. New Orleans and Atlanta have both decriminalized marijuana.

Legalization Has No Negative Impact on Youth Use, Public Safety

Researchers with the Cato Institute concluded in 2016 that state marijuana legalizations have had a minimal effect on marijuana use. Later, researchers with the Drug Policy Alliance arrived at the same conclusion.

“Youth marijuana use has remained relatively stable in the past several years, both nationwide and in states with established marijuana regulatory programs,” reported the Drug Policy Alliance, which looked at data from Washington, Colorado and Alaska. “These results are promising, suggesting that fears of widespread increases in use have not come to fruition.”

The Cato Institute examined data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey – Past Month Marijuana Use chart from Alaska and Colorado. The data shows little change in Alaska since 1995 and show a drop in the rate of youth marijuana usage – from nearly 30 percent to less than 25 – in Colorado between 1995 and 2015.

Cato researchers also examined standardized test scores from Washington to look for negative impacts that could be tied to legalization. They found none. “Standardized test scores measuring the reading proficiency of 8th and 10th graders in Washington State show no indication of significant positive or negative changes caused by legalization,” the researchers wrote. “Although some studies have found that frequent marijuana use impedes teen cognitive development, our results do not suggest a major change in use, thereby implying no major changes in testing performance.”

As for use among adults, the data show marijuana use was undergoing a modest increase even before legalization. The rise, the Cato researchers pointed out, might have been as much a cause of legalization as an effect of it.

“The key fact is that marijuana use rates were increasing modestly for several years before 2009, when medical marijuana became readily available in dispensaries, and continued this upward trend through legalization in 2012,” the researchers wrote. “Post-legalization use rates deviate from this overall trend, but only to a minor degree. The data do not show dramatic changes in use rates corresponding to either the expansion of medical marijuana or legalization.”

DUIs decrease, no evidence of rise in increased crime

Under the influence of marijuana, a driver may experience slowed reaction time, impaired coordination and distorted perception. Fortunately, research indicates that legalization has not led to an increase in traffic fatalities in states that have adopted it.

The Cato Institute examined data from Colorado and Washington in 2015. “No spike in fatal traffic accidents or fatalities followed the liberalization of medical marijuana in 2009,” Cato reported. “Although fatality rates have reached slightly higher peaks in recent summers, no obvious jump occurs after either legalization in 2012 or the opening of stores in 2014. Likewise, neither marijuana milestone in Washington State appears to have substantially affected the fatal crash or fatality rate.”

The Drug Policy Alliance’s more recent report explored the issue as well. In fact, researchers discovered that arrests for driving under the influence – for any substance – were down since 2011.

“According to the Colorado Bureau of Investigation, the number of DUI citations issued statewide declined by 16 percent from 26,146 in 2011, the last year prior to legalization, to 21,953 in 2016, the second year after legal sales of adult use marijuana began,” the Drug Policy Alliance said. However, it should also be noted that there is no accurate test to determine whether a driver is under the influence of marijuana at a roadside stop, according to the CDC.

In Washington, DUI arrests fell by almost one-third. It wasn’t just that arrests for DUIs were down. In an earlier report, the Drug Policy Alliance found that all drug-related crime in Colorado decreased by 23 percent. “This underscores the central role of marijuana prohibition in the drug war, as well as marijuana legalization’s implications for criminal justice reform more generally,” the researchers wrote.

This conclusion was supported by Cato’s research. “For all reported violent crimes and property crimes [in Denver], both metrics remain essentially constant after 2012 and 2014; we do not observe substantial deviations from the illustrated cyclical crime pattern,” they reported.

Thus, while fears of increased marijuana use, traffic fatalities and crime have not materialized, states have seen tremendous new revenue generated to support education, drug treatment programs and other essential government services.

Recommendations

As this report illustrates, marijuana prohibition in Alabama is costly – both in fiscal and human terms. The state’s laws are overly harsh and ill-defined, drawing thousands of people each year into the overburdened criminal justice system and creating uneven justice. In addition, prohibition is disproportionately enforced on black communities, continuing a long legacy of racial discrimination in Alabama. In the meantime, nine states and the District of Columbia have legalized adult use of marijuana. There has been no evidence of harm to public health or safety in those states. In fact, those states are reaping billions in taxes, creating new jobs and seeing evidence of public safety improvements. Most other states have either approved medicinal marijuana or decriminalized possession. It’s time for Alabama to join a growing national consensus on the safety of marijuana and shed the costly, counterproductive laws that grew out of the failed War on Drugs. The following recommendations offer a roadmap to reform.

For Legislators

Legalize the possession and personal use of marijuana by adults

Without jeopardizing public safety, the legalization of marijuana for personal use and the possession of drug paraphernalia would substantially reduce criminal justice-related expenditures, raise substantial new revenue and begin to address the racial disparities that permeate Alabama’s criminal justice system. More than one in five people in the United States live in a jurisdiction that has legalized the use of marijuana by adults. Estimates predict that the nationwide legalization of marijuana would generate $132 billion in new tax revenue over the next decade, create 1.1 million new jobs by 2025 and reduce criminal justice expenditures by billions of dollars. At the same time, drunk-driving arrests in Washington and Colorado – the first states to create regulated markets – are down. In a state with structural budget gaps, a bloated criminal justice system, and substantial racial disparities from arrests to incarceration, Alabama lawmakers should legalize the recreational use of marijuana by adults and the possession of drug paraphernalia and use the tax revenue to fund programs like behavioral health and alcohol and drug treatment, school counselors, community-based medical care and K-12 education.

Reclassify the possession and personal use of marijuana as a civil offense

Short of legalization, Alabama should stop needlessly ensnaring thousands of Alabamians in its criminal justice system each year. Each year, Alabama wastes approximately $22 million enforcing its marijuana possession laws. In 2016, there were 2,351 marijuana possession arrests – 23 percent of all drug arrests. Even a conviction for the possession of a small amount of marijuana, whether charged as a misdemeanor or felony, will have effects that last a lifetime, limiting access to student financial aid, housing and employment. Enforcement falls disproportionately on African Americans, who are 4.1 times as likely to be arrested for possession despite robust evidence that white and black people use marijuana at roughly the same rate. And it is not just the human cost that harms Alabama. Alabama lawmakers should reclassify one ounce or less of marijuana as a civil offense.

Reclassify the possession of drug paraphernalia as a civil offense

Alabama should remove the possession of drug paraphernalia from its criminal code. Alabama’s paraphernalia laws are broadly drafted, leaving law enforcement with substantial discretion which, as with other offenses, disproportionately harms people of color. In addition, the items considered to be paraphernalia include numerous items that can be legally purchased in Alabama and other states.

Eliminate fines and fees for offenses related to the possession and personal use of marijuana and drug paraphernalia

Short of legalization, Alabama must end the hidden tax system that falls disproportionately on those who cannot afford to pay. For example, a misdemeanor marijuana possession conviction carries with it at least $214 in fees and a potential fine up to $6,000. These court-imposed fines and fees serve no public safety purpose, and instead exist to fill budget gaps created by Alabama’s regressive tax system. Alabama lawmakers must eliminate these fines and fees and ensure that government spending decisions occur through an open and transparent state budgetary process.

Mandate an ability to pay determination for fines and fees for offenses related to the possession and personal use of marijuana and drug paraphernalia, and scale accordingly

Short of ending fines and fees, Alabama must stop assessing fines and fees against people who have no realistic ability to pay them. These are lose-lose situations. As Alabama Appleseed documented in Under Pressure: How fines and fees hurt people, undermine public safety, and drive Alabama’s racial wealth divide, people will take drastic measures to repay their fines and fees, including forgoing basic necessities, taking out predatory loans and even committing crimes. This makes Alabamians less safe, traps poor Alabamians in a cycle of debt, and harms not only the individuals charged but their children and other family members. Alabama lawmakers must ensure that people who cannot afford fines and fees are not assessed fines and fees, and that those who can afford fines and fees are assessed at a rate proportional to their ability to pay.

Create clearly defined and appropriate weight thresholds

Short of legalization, Alabama must clearly define its marijuana weight thresholds and create a more appropriate weight threshold for triggering a marijuana trafficking offense. Alabama law lacks weight thresholds to distinguish between marijuana possession and distribution, and allows substantial discretion and a low threshold to trigger marijuana trafficking. Together, these gaps result in uneven justice in the enforcement of Alabama’s marijuana laws. For example, Person A and Person B can be arrested for possession of the same amount of marijuana under the same circumstances, and face very different punishments based on the subjective decision of an elected district attorney. Alabama lawmakers should create clearly defined, reasonable, evidence-based policy solutions, including weight thresholds that distinguish between marijuana possession, distribution and trafficking.

Mandate the collection and publication of stop and arrest data by race

Alabama’s marijuana laws are enforced along color lines, yet Alabama law enforcement agencies are not required collect and make public their interactions with community members. Alabama law enforcement should be required to collect and make public information concerning all stops and arrests by law enforcement, including the race, gender, age and ethnicity of both the officer and community member. This information should also include whether the stop or arrest was officer- or community-initiated and the outcome of each stop. Basic transparency will better ensure that law enforcement is accountable to the people and that law enforcement leadership has the information necessary to effectively manage officers. Alabama lawmakers should mandate the collection of police interaction data, including basis for stop, race of officer and subject, and outcome.

End civil asset forfeiture

Civil asset forfeiture has evolved from a program intended to strip illicit profits from drug kingpins into a revenue-generating scheme for law enforcement that is widely used against people – disproportionately African-American – accused of low-level crimes or no crime at all. In 55 percent of the civil asset forfeiture cases where criminal charges were filed in 2016, the charges were related to marijuana. In 18 percent of cases where criminal charges were filed, the charge was simple possession of marijuana and/or paraphernalia. Alabama lawmakers should require that the forfeiture process occur within the criminal case and prohibit the use of criminal forfeiture in cases involving marijuana or drug paraphernalia possession, as marijuana or drug paraphernalia possession necessarily means there was no ill-gotten profit. This mandate means the government must prove that the individual whose property was taken was actually convicted of a crime beyond a reasonable doubt, and that the property seized was the product of, or that it facilitated, that crime.

For District Attorneys

Exercise discretion to stop prosecuting marijuana possession and drug paraphernalia arrests

Each year, Alabama’s district attorneys request additional funds from the legislature yet continue to spend valuable financial and staffing resources prosecuting individuals for the mere possession of marijuana or paraphernalia. District attorney docket sizes and expenditures, as well as the Department of Forensic Sciences backlog on evidence related to serious crimes, would be substantially reduced if district attorneys focused on serious criminal matters rather than a substance that can be legally used by Alabamians traveling through nine other states or the District of Columbia. We urge district attorneys to use discretion and stop prosecuting marijuana possession offenses.

Diversion Programs Not a Remedy for Harsh Marijuana Laws

Diversion programs are often touted as a remedy to harsh drug laws – a second chance. In reality, they typically come with high entry fees and difficult schedules that allow those with money and flexible employment to enter the program but effectively deny that opportunity to those less fortunate.

Not all diversion programs are bad, but they are hardly a remedy to Alabama’s destructive marijuana laws.