Shadow of Jim Crow: Georgia activists fight for voting rights for people with felony convictions

They met in a prison choir called, in what now seems like prophecy, Voices of Hope.

One 20 years old and the other just 15 when they were convicted of felony crimes, Page Dukes and Kareemah Hanifa didn’t have much hope when they landed at the largest women’s prison in Georgia. Even when they both gained coveted places in the chorus, entitling them to travel outside prison walls to performances around the state, the confidences they shared on long bus rides about what they would do when they got out seemed, Hanifa recalled, like daydreams.

But today Hanifa, 44, and Dukes, 35, are not only out of prison but fulfilling their personal ambitions. Hanifa is a bachelor’s degree candidate in psychology on track to pursue a master’s degree; Dukes is a communications associate with a nonprofit.

They are now lifting their voices in a new way.

The longtime friends are among the leaders of a growing movement in Georgia to secure the right for people with felony convictions to do something the U.S. Constitution is supposed to guarantee all its citizens – vote.

“Why shouldn’t I be allowed to cast a ballot and have a say in my government?” Hanifa said of criminal disenfranchisement laws that block her and 5.2 million other people across the country with felony convictions from the ballot box. Almost 275,000 of those citizens live in Georgia, according to the Sentencing Project, which tracks such laws. Of those, nearly 60% are Black.

“OK, I committed a crime,” Hanifa said. “I served my time in prison. But then for 50 more years am I still being penalized? Did society forgive me? Or not? Or am I still being punished? You forgave me enough to release me from that physical prison, but not from that barless prison that holds people like me back from the power to have our say in our communities, to have something to say about education, about who represents us.”

Working with community organizations like the Southern Center for Human Rights, where Dukes is employed, and the Inner-City Muslim Action Network, where Hanifa is the lead organizer, the Southern Poverty Law Center is organizing a legislative campaign to restore voting rights for Georgians with felony convictions.

Relics of Jim Crow

While dozens of countries allow all people held in prison to vote, only two states, Vermont and Maine, as well as Washington, D.C., do so in the U.S. And in 11 states, people lose their voting rights even after they have been released. In Georgia, the ban lasts through probation and parole or supervision, which can extend decades after serving time. Even registering to vote could land you back in jail.

In Georgia, the largest factor for disenfranchisement is the number of people on probation. Georgia’s probation rate is the highest in the U.S., with 1 in 17 adults on probation. This is nearly double the probation rate of Idaho, the state with the second-largest probation rate, and more than triple the national rate.

The actual wording of the law in Georgia bans voting for people convicted of felonies “involving moral turpitude.” But because the law fails to define what moral turpitude is, in practice it applies to all felony convictions.

Further, because the state requires formerly incarcerated people to satisfy their legal financial obligations before terminating their parole and probation, Georgia has the highest rate of people under supervision due to felony convictions in the country. The majority of people under supervision are individuals convicted of nonviolent crimes, such as property and drug offenses.

Disenfranchisement laws are relics of the Jim Crow era, when lawmakers in Southern states used them to suppress the voting power of African American men who had gained the right to vote. In recent years, as the country wrestles with its legacy of racism and inequality, some states scaled back felony disenfranchisement.

In 2020, Iowa became the most recent state to lift what had been a lifetime ban. In Florida, a massive volunteer effort led by a formerly incarcerated man, Desmond Meade, resulted in voters approving a 2018 referendum restoring eligibility to people who are off probation or parole. Amendment 4 re-enfranchised as many as 1.5 million people in the state.

But soon after the referendum passed, its reach and effectiveness were undercut by the Republican-dominated Legislature, which passed a bill – signed into law by Gov. Ron DeSantis – making the right to vote for people with past felony convictions contingent on full payment of a labyrinth of fees and restitution.

‘Restoring dignity’

In Georgia, Dukes, Hanifa and others advocating for rights restoration have a steep hill to climb. The state has the ninth-highest rate of incarceration in the nation. And Black people in Georgia are incarcerated at more than three times the rate of their white counterparts.

Two pieces of legislation on rights restoration were never even heard in committee or considered by the Legislature: One, introduced in 2019, would reduce the types of felonies considered crimes of “moral turpitude”; the other, introduced last year, proposed a constitutional amendment that would restore voting rights to state residents convicted of a felony.

“If you are a citizen of the United States, you should not lose your right to vote,” said John Paul Taylor, rights restoration field director for the SPLC’s Voting Rights Practice Group.

Taylor is leading the SPLC’s efforts to lobby for legislation that would remove the moral turpitude clause in Georgia.

“Every citizen of voting age deserves the ability to make the choice for who represents them,” Taylor said. “It should not be something that is stripped away. If you strip voting rights, that is central to stripping other rights away. So, restoring the right to vote is not just about passing a law, it’s really about restoring dignity and a sense of personhood.”

Dignity. Personhood. That is what Dukes began to feel keenly deprived of in the summer of 2020.

Convicted of armed robbery at age 20, Dukes had spent an entire decade in prison. But she had worked hard to conquer the substance use disorder that derailed her adolescence.

She was released from prison in 2017. First in prison and then while living in a halfway house, she attended university, eventually earning a dual Bachelor of Arts degree in mass communications and philosophy and religion at Piedmont College. She interned at the Marshall Project, where she wrote and edited stories for the “Life Inside” series. And she secured first an internship at the Southern Center for Human Rights, then a full-time job in communications.

By the summer of 2020, she was on unsupervised probation, able to leave the state without permission, “so I had no tangible evidence of still being under correctional control.” Dukes said. “However, I didn’t have the right to vote.”

That summer, when people were out in the streets protesting police brutality in the months following George Floyd’s murder, “it really struck me that I couldn't be there,” Dukes said. “There were curfews. People were being arrested for just being out in a car. And I was fearful to even go out of my house after 8 o’clock because I knew that if I was arrested, I would be going back to prison. So, not only was it the right to vote that had been taken away from me, but also my First Amendment rights? It was really at this point that I felt I had to do something.”

Dukes was lucky. A lawyer at the Southern Center for Human Rights helped guide her through the process of filing a motion seeking early termination of her probation. A judge granted the motion, and she was able to register and vote in the November 2020 general election and then again in the Senate special election in Georgia in January 2021.

Dukes emerged grateful to have her right to vote restored. But the ordeal, she said, opened her eyes to the scope of the issue of felony disenfranchisement.

“I don’t think anyone should ever lose the right to vote,” Dukes said. “People who are in prison are counted in the census. And yet the people who represent those districts don’t see them as their constituents because they don’t have the power to vote or have any say in policy decisions that really affect them and their families and their communities.

“And then even after we are released and we are paying taxes and working and contributing to our communities, we are still unable to have any recognition by our elected leaders or any say in policies,” Dukes said. “It’s a very offensive message that you are an outcast, that you are less than a citizen.”

‘Voice for the voiceless’

Kareemah Hanifa spent years feeling like an outcast. Sentenced to life in prison at age 15 for charges of murder and kidnapping, she said she thought she had made a mistake that would leave her behind bars for the rest of her life.

But Hanifa grew up in prison. Incarcerated for 26 years, she took classes, joined the choir and most importantly became an advocate for incarcerated people who were ill or needed help. Her record made parole a possibility, and she began to dream about what she would do if she were released.

“The last two years of my life in prison I was like, I’m going to come out and I’m going to be the voice for the voiceless,” Hanifa said. “I made a promise to God and to my peers at that time. I said, if they ever let me go, I’m going to go out and I’m going to talk about the issues that directly affect women that are incarcerated. And I actually came home, and I did.”

Fittingly, it was at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, famous as the church where Martin Luther King Jr. and his father were pastor and co-pastor, that Hanifa met the man she would later marry. They were speakers at a workshop devoted to ending mass incarceration. In the years since, they have devoted their lives together to that cause.

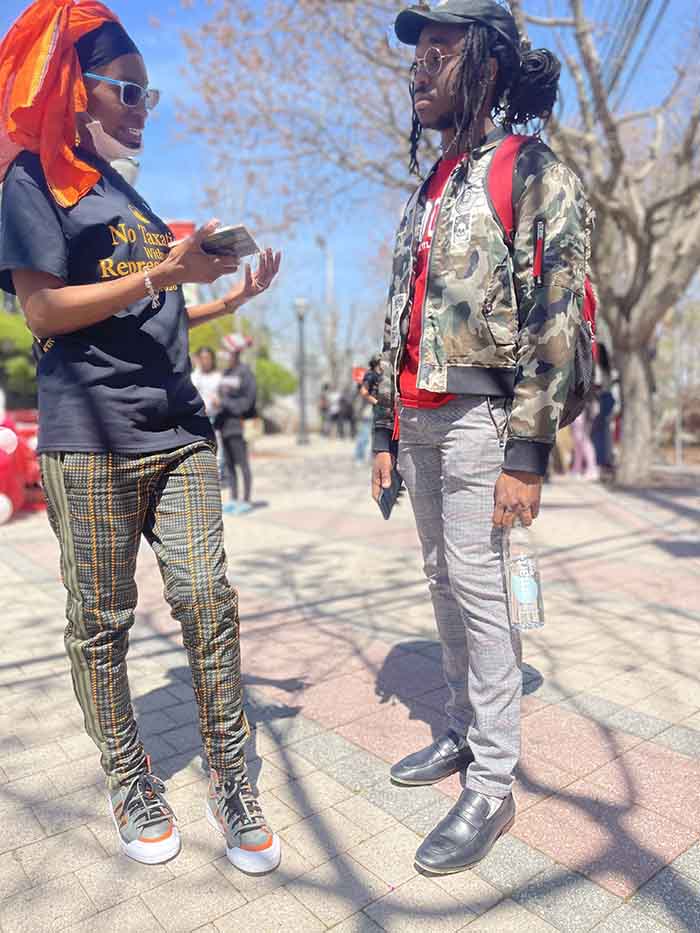

On parole for the rest of her life, Hanifa is unlikely ever to be able to vote. But she says she is determined to work to restore that right for others. When she is not studying, she joins other activists gathering signatures to try to get a referendum on the ballot to end felony disenfranchisement. She meets with lawmakers at the state Capitol. She canvasses at historically Black colleges and universities.

At every turn, she says, she asks herself one question: Why is so much being done to block citizens from accessing the vote?

“Our endgame is to have a law written that allows individuals who are taxpayers access to the voting system to participate in choosing who our leadership is,” Hanifa said. “I pay bills. I live here. I’m a real person. I pay taxes, I am law abiding. But because I am still on supervision, I am not allowed to decide who the governor, president, sheriff or mayor will be. How can these individuals represent my best interests if they are not chosen by people like me? Why is this not simple?”

Top picture: Kareemah Hanifa, center, marches with Georgia State Sen. Nan Orrock, center left, and Atlanta NAACP President Richard Rose, center right, during a voting rights demonstration on April 12, 2022, in Atlanta. (Contributed by Inner-City Muslim Action Network)