Mississippi’s Broken Education Promise – A Timeline

The promise of an education in Mississippi’s constitution is among the weakest in the nation.

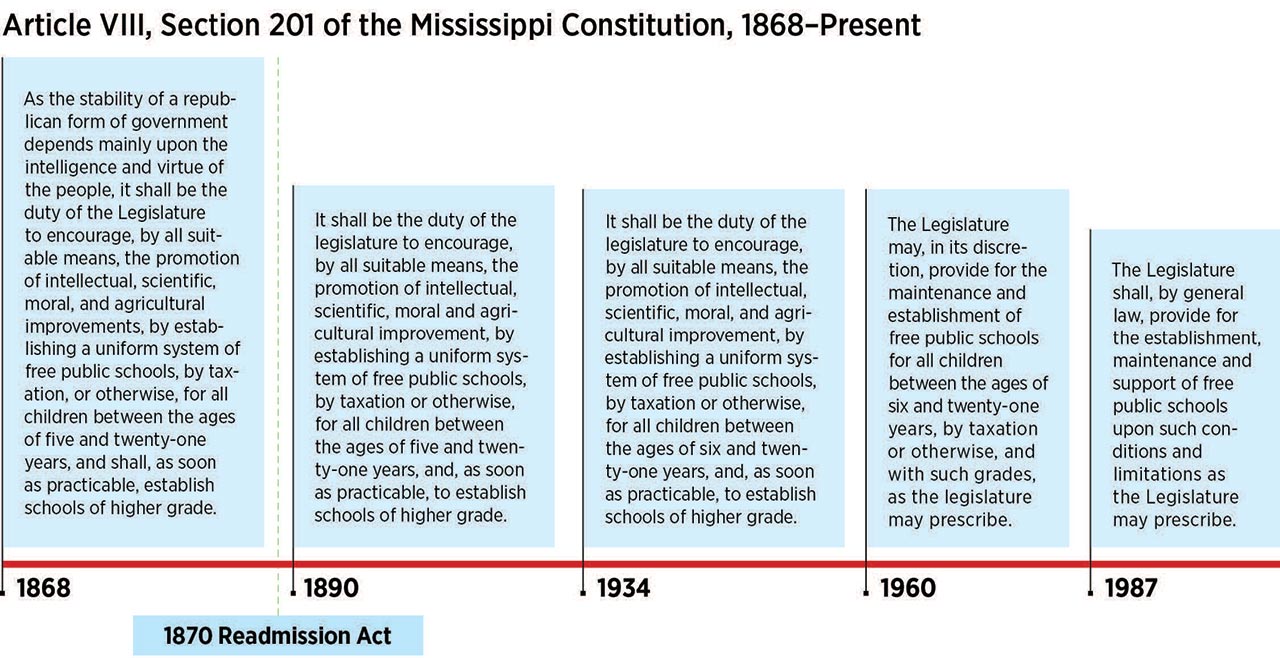

It hasn’t always been this way. When the state was readmitted to the Union after the Civil War, its constitution included a strong education clause that guaranteed a “uniform system of free public schools” for all children – regardless of race. Under the terms of readmission, that promise could not be diminished.

Mississippi, however, has violated the provision by amending its education clause four times and providing inferior educational opportunities to its black students.

The changes began at the start of the Jim Crow era as part of the broader white supremacist movement to dismantle the rights of former slaves and their descendants.

As a result of the amendments, generations of Mississippi’s children – both black and white – have been short-changed. Today, the state’s public schools are poorly funded and anything but “uniform.”

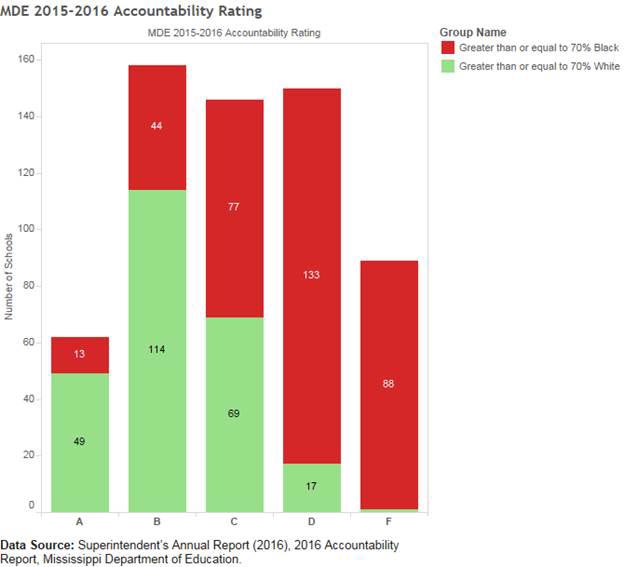

As was expressly intended by the first change in 1890, the harm has fallen most heavily on African-American children. All of the state’s “F”-rated school districts are majority-black. Conversely, the vast majority of “A”-rated schools are at least 70 percent white. Last year, the Mississippi Department of Education reported a 29 percent achievement gap between black and white students.

The SPLC filed a federal lawsuit in May 2017 accusing the state of repeatedly violating the education promise enshrined in its post-Civil War constitution and in the 1870 congressional act that allowed it to rejoin the Union. The following timeline chronicles the history that has led to this moment.

December 10, 1817 – The state of Mississippi is admitted to the Union. Its economy is powered by slave labor, and cotton is king.

1860 – There are 436,631 slaves in Mississippi – comprising about 55 percent of its population.

January 9, 1861 – Following the election of Abraham Lincoln, Mississippi becomes the second state to secede from the Union. Its Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union states:

Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. That blow has been long aimed at the institution, and was at the point of reaching its consummation. There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin.

February 4, 1861 – Mississippi and six other states form the Confederate States of America.

February 18, 1861 – Jefferson Davis, a slave owner who operates a cotton plantation in Mississippi, is inaugurated as the president of the Confederacy.

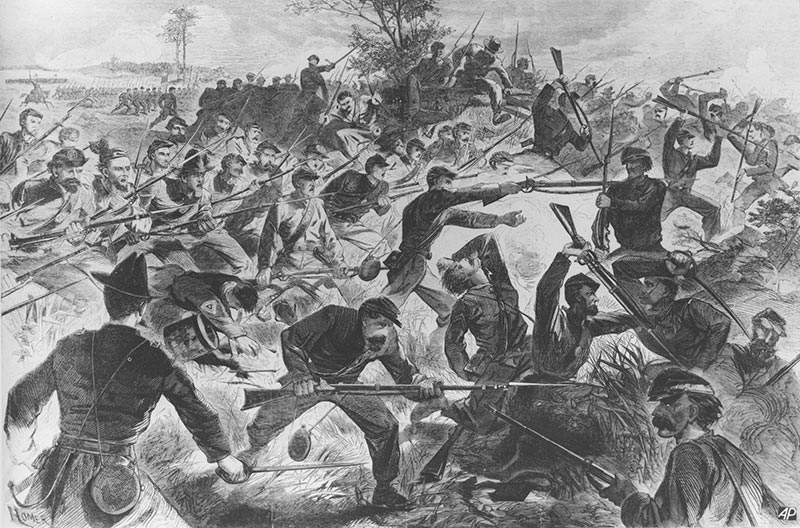

1861 to 1865 – American Civil War – Eighty thousand Mississippians fight to maintain slavery. Casualties are heavy.

July 4, 1863 – The Army of Mississippi surrenders following the pivotal siege of Vicksburg.

May 4, 1865 – The remnants of the Confederate army in the Western Theater surrender.

May 9, 1865 – President Andrew Johnson declares that armed resistance and insurrection against the United States is “virtually at an end.”

May 10, 1865 – Jefferson Davis is captured.

1865 – Mississippi becomes the first state to enact Black Codes that restrict the rights and status of African Americans after the Civil War. Other former Confederate states soon follow.

March 2, 1867 – The Military Reconstruction Act divides the South into districts under federal military command. Former Confederate states wishing to end Reconstruction and rejoin the Union must ratify the 14th Amendment, hold a constitutional convention and adopt a constitution consistent with the U.S. Constitution. State constitutions must be approved by Congress.

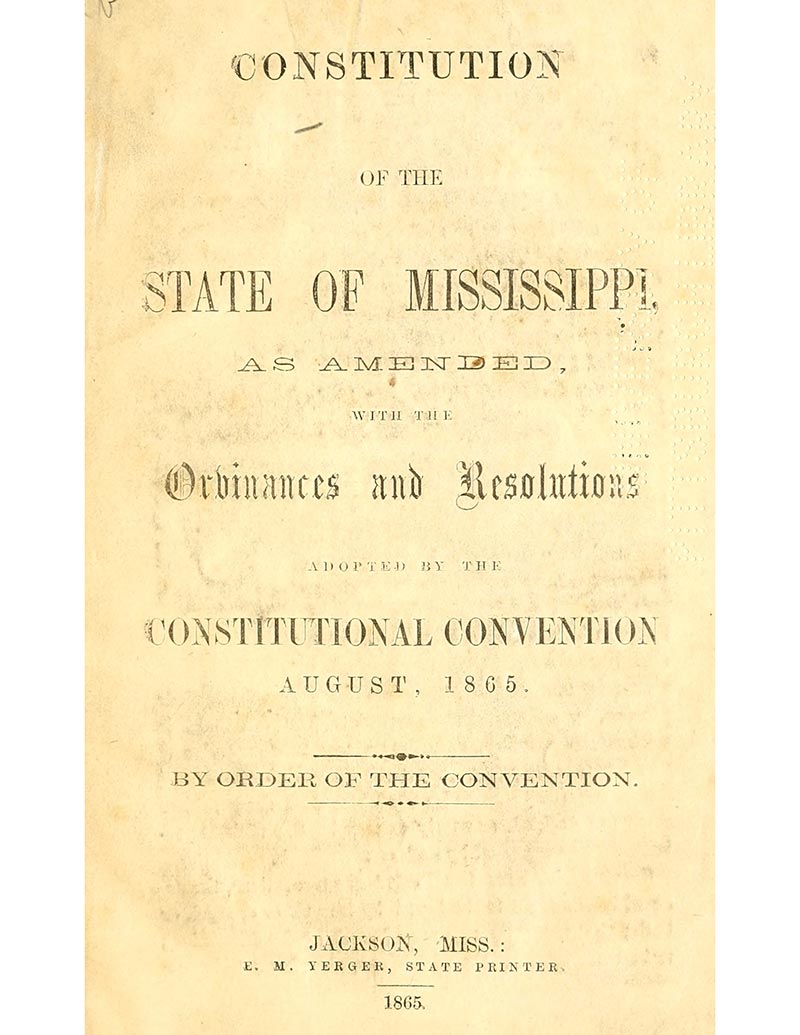

January 1868 – One hundred delegates, including 17 African Americans, gather for a constitutional convention, leading it to become known as the “Black and Tan Convention.” It is the first time that African Americans participate in the political process in Mississippi. The new constitution includes a strong clause requiring the state to provide an education for all children, regardless of race:

As the stability of a republican form of government depends mainly upon the intelligence and virtue of the people, it shall be the duty of the Legislature to encourage, by all suitable means, the promotion of intellectual, scientific, moral, and agricultural improvements, by establishing a uniform system of free public schools, by taxation, or otherwise, for all children between the ages of five and twenty-one years, and shall, as soon as practicable, establish schools of higher grade.

April 10, 1869 – Congress approves the new Mississippi Constitution.

January 17, 1870 – Mississippi ratifies the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

Feb. 23, 1870 – Mississippi is readmitted to the Union. Congress returns Mississippi to full statehood by passing the “Readmission Act.” In an attempt to protect the rights of freed slaves, the Act provides that “the [1869] state constitution may not be amended or changed to deprive any U.S. citizen, or class of citizens, the school rights and privileges secured under the constitution, or to deny the right to vote to any eligible U.S. citizen or class of citizens.” It also bars Mississippi from enacting any law to deprive any citizen of the right to hold office based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude, or any other qualifications for office not required of all other citizens.

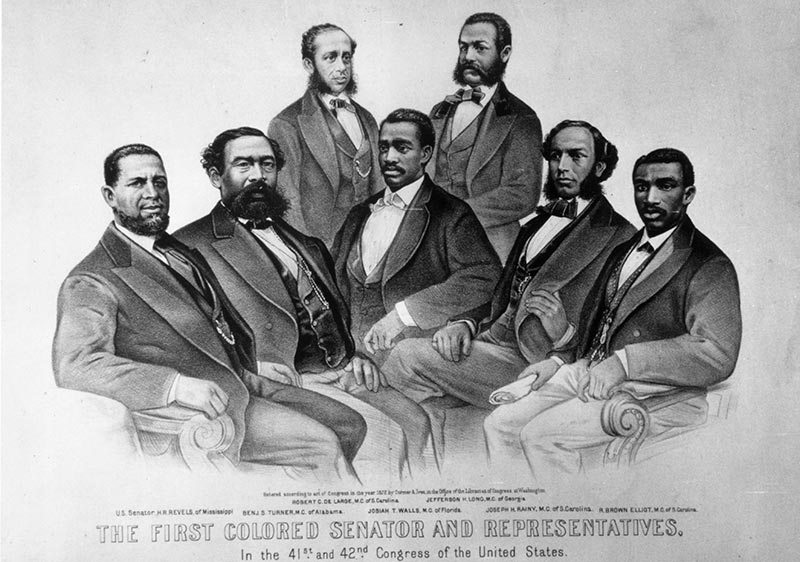

1869 to 1875 – Empowered by the protections of the Readmission Act, African Americans register to vote and leverage their new political status to craft more favorable public policy to help them achieve equity in terms of community services, the courts, police protection, and freedom of expression and movement. By 1875, one-third of the Mississippi Senate and 59 members of the House of Representatives are African-American. Black men also serve as superintendent of education, lieutenant governor, secretary of state and speaker of the House. African Americans play a leading role in pushing for the development of a uniform system of public schools, which serves as an incubator for a new generation of black men and women equipped with the rights to vote, negotiate labor agreements, own land and participate in the political process.

1875 – Upset by the gains of former slaves, white supremacists launch a campaign of violence, fraud and intimidation during the 1875 election. It is part of the so-called “Redemption” movement that sweeps the South and eventually leads to the adoption of Jim Crow laws that reinstitute racial segregation across the region. Goaded by local newspapers and political leaders, young white men form armed militias to intimidate black voters. A congressional report later describes it as an attempt to “inaugurate an era of terror” to prevent African Americans from “the free exercise of the right to vote.” White Democrats easily gain control of both houses of the Legislature. By 1890, only four African Americans still serve in the Legislature. Whites also regain control of other political offices. A new, white education superintendent declares that the creation of public schools was “an unmitigated outrage upon the rights and liberties of the white people of the state.” Lawmakers drastically reduce taxes and state expenditures in all areas, including public education.

1878 – Though school segregation is already a fact of life in Mississippi, lawmakers write it into state law by requiring “that the schools in each county shall be so arranged as to offer ample free school facilities to all educable youths in that county but white and colored children shall not be taught in the same school-house, but in separate school-houses.”

August 1890 – A constitutional convention meets to further disenfranchise the state’s black residents. Judge S.S. Calhoon, the convention president, proclaims, “We came here to exclude the negro. Nothing short of this will answer.” Throughout the convention, the Jackson Clarion-Ledger reports the sentiment is shared by nearly the entire delegation. W.S. Eskridge, a Tallahatchie County delegate, declares: “The white people of the state want to feel and know that they are protected not only against the probability but the possibility of negro rule and negro domination. … The remedy is in our hands, we can if we will afford a safe, certain and permanent white supremacy in our state.” A decade later, future Gov. James Vardaman describes the intent in the most honest terms: “There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter. Mississippi’s constitutional convention of 1890 was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the nigger from politics; not the ‘ignorant and vicious,’ as some of those apologists would have you believe, but the nigger. … Let the world know it just as it is.”

Nov. 1, 1890 – Mississippi adopts new a constitution that greatly diminishes the political power of African Americans by restricting their voting rights. It also creates racially segregated schools and a new school funding mechanism that allows wealthy, white school districts to levy taxes for education revenue far in excess of the taxes generated in poor, largely African-American districts.

1899 – The state school superintendent says, “It will be readily admitted by every white man in Mississippi that our public school system is designed primarily for the welfare of the white children of the state, and incidentally, for the negro children.”

1934 – Mississippi violates the Readmission Act by raising the minimum age for public school from 5 to 6. The Depression-era measure, according to the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, “was urged by school officials as a means of saving the state many thousands of dollars.”

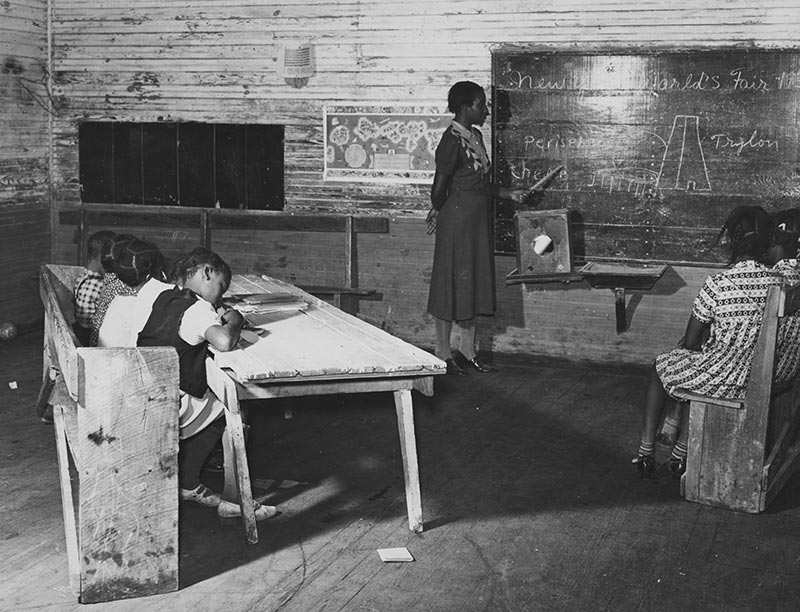

1944 to 1954 – A decade before the U.S. Supreme Court declares segregated schools unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education, white Mississippians begin to recognize that ensuring black schools are equal to white schools may be the best way to fend off lawsuits that could end segregation. A 1952 state report, however, finds vast disparities between black and white schools; a Delta district, for example, spends $464.49 per white student but only $13.71 per black student.

May 17, 1954 – The U.S. Supreme Court declares segregated schools unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education. The unanimous decision finds that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

1960 – The Mississippi Legislature declares the Brown decision unconstitutional and enacts a statute allowing school boards to close schools and transfer students out of districts in order to maintain “public peace, order or tranquility.”

1960 – Mississippi violates the Readmission Act again by amending its constitution to further dilute the education clause. To avoid desegregation mandates flowing from Brown v. Board of Education, the state amends its constitution to make free public schools a discretionary function of the Legislature. The modified clause states:

The Legislature may, in its discretion, provide for the maintenance and establishment of free public schools for all children between the ages of six and twenty-one years, by taxation or otherwise, and with such grades, as the legislature may prescribe.

1987 – Mississippi amends its education clause again in violation of the Readmission Act. The revision, presented as an attempt to remedy what has been described as the “historical embarrassment” of the 1960 measure, also strikes language establishing a minimum and maximum age for school attendance and other provisions – further eviscerating the original education clause. The clause still stands in this form today:

The Legislature shall, by general law, provide for the establishment, maintenance and support of free public schools upon such conditions and limitations as the Legislature may prescribe.

Aug. 22, 1997 – Lawmakers pass the Mississippi Adequate Education Program (MAEP) to fund education. Designed to address low student achievement and inequality between school districts, MAEP establishes a school funding formula that calculates the amount of money purportedly needed each year to provide an adequate education. Each district is required to provide a portion of the base cost, leaving the state to cover the rest.

2014 – Mississippi voters gather nearly 200,000 signatures to place Initiative 42 on the 2015 ballot. Almost 20 years after the passage of the Mississippi Adequate Education Program, it has been fully funded only twice, leaving schools in poor districts to suffer. Initiative 42 is a proposed constitutional amendment requiring the Legislature to fully fund the program. Opponents warn that it would open the state up to lawsuits. In a speech to the Tishomingo County Midway Republican Rally shortly before the vote, state Rep. Bubba Carpenter, who is white, puts the argument in explicitly racial terms: “If 42 passes in its form, a judge in Hinds County, Mississippi, predominantly black – it’s going to be a black judge – they’re going to tell us where the state education money goes.”

Nov. 3, 2015 – Initiative 42 fails. Certified vote totals show 51.6 percent of voters cast a ballot not to amend the state constitution, killing the initiative.

October 2016 – State data shows that Mississippi’s failing school districts are overwhelmingly black. The Mississippi Departmentof Education’s school district evaluation shows that 13 of the state’s 19 “F”-rated districts are more than 95 percent black. The remaining six range from 80.5 percent to 91 percent black. The state’s top five highest performing school districts are predominantly white.

November 2016 – The state reports a vast racial achievement gap. Data from the Mississippi Department of Education show a 28.6 percent achievement gap between black and white students in English language arts and a 27.8 percent gap in math.

2017 – Mississippi’s schools are among the least effective in the country and continue to fail children because of the erosion of the education clause. The most vulnerable children are deprived of the same educational opportunities available to others. Despite the Mississippi Adequate Education Program, public schools have been underfunded by nearly $2 billion over the previous nine years. The five states that rank highest in academic achievement spend a total of between $14,150 and $17,300 per student. Mississippi spends just $9,394. The state’s black students continue to face a racial achievement gap.

May 23, 2017 – The SPLC files a federal lawsuit accusing Mississippi of breaking the education guarantee contained in its first constitution. The complaint describes how four amendments to the 1868 education clause have diminished the education rights of Mississippi citizens in violation of the Readmission Act that allowed the state to rejoin the Union.