Randy Weaver, Influential Figure for White Supremacist, Militia Movements, Has Died

Randy Weaver, whose deadly 1992 standoff with the U.S. government made Ruby Ridge a rallying cry for antigovernment and white nationalist movements throughout ensuing decades, died at his home in Montana on May 11, according to social media posts made by his daughter, Sara Weaver. He was 74.

During an 11-day armed siege beginning on Aug. 21, 1992, Weaver and his family held off federal agents who were surrounding their off-grid cabin in remote Boundary County, Idaho. By Aug. 23, U.S. Marshal William Francis Degan, Weaver’s son, Sammy, and his wife, Vicki, had all been shot dead. Weaver and his three daughters finally surrendered on Aug. 31.

Even as the siege unfolded, far-right activists flocked to Ruby Ridge in support of Weaver in his confrontation with the U.S. government. In the following half-decade, the Weavers’ story fueled the growth of a burgeoning antigovernment militia movement, and some on the radical right used the events to justify acts of domestic terrorism. They included Timothy McVeigh – who portrayed his 1995 bombing of a federal government building in Oklahoma City, which killed 168, including 19 children, and injured 759 others – as an act of revenge for Ruby Ridge and the deadly 1993 confrontation between federal agents and the Branch Davidian group in Waco, Texas.

Randall Claude Weaver was born on Jan. 3, 1948, to a farming family in Villisca, Iowa. From 1968 to 1970, he served in the U.S. Army’s Special Forces. Back in Iowa, he took a well-paid factory job and married another local, Vicki Jordison, in 1971.

Together, the Weavers began to embrace fundamentalist Christian beliefs. From the mid-1970s, Randy and Vicki claimed to have had religious visions, and they voraciously consumed conspiracist literature with antisemitic and apocalyptic overtones. In 1983, they left for Idaho to wait out the tribulation that they believed would soon destroy a corrupt modern America and herald Christ's return.

That fall, they found a patch of land on Ruby Ridge, near Naples, Idaho, and by March 1984, they had built a rough cabin and moved in. The Weavers did not relocate alone. In the early 1980s, Boundary County and other parts of North Idaho saw an influx of radical rightists, religious fundamentalists, survivalists and others who sought to live apart from a secular, liberal America they despised.

Just an hour’s drive from the Weavers’ cabin, in Hayden Lake in neighboring Kootenai County, Richard Girnt Butler presided over the Aryan Nations compound, where residents and visitors from the broader White Power movement looked forward to the creation of a separatist white homeland in the Pacific Northwest.

Randy Weaver’s story would soon become fatally entangled with that of the compound.

Butler was a preacher in the Christian Identity movement, whose adherents usually affirm a twisted, white supremacist interpretation of Christian scripture that asserts that Jews are satanic, and that Black people emerged from a separate, inferior creation. Once in Idaho, the Weavers, too, adopted Christian Identity beliefs.

The couple homeschooled their children and took in another teenager, Kevin Harris. In 1988, Randy Weaver made an abortive run for Boundary County sheriff on an extremist platform rooted in Posse Comitatus ideas, yet another strain of far-right ideation that has led to loss of life during standoffs with law enforcement. Weaver and his family attended gatherings at the Aryan Nations compound where Weaver expressed antisemitic beliefs.

In October 1989, Weaver sold two illegal sawed-off shotguns to an undercover agent from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF). In June 1990, the ATF attempted to use the sale to pressure Weaver into becoming an informant and assisting their ongoing efforts to prosecute Richard Butler and other Aryan Nations members. When Weaver refused, the ATF filed charges.

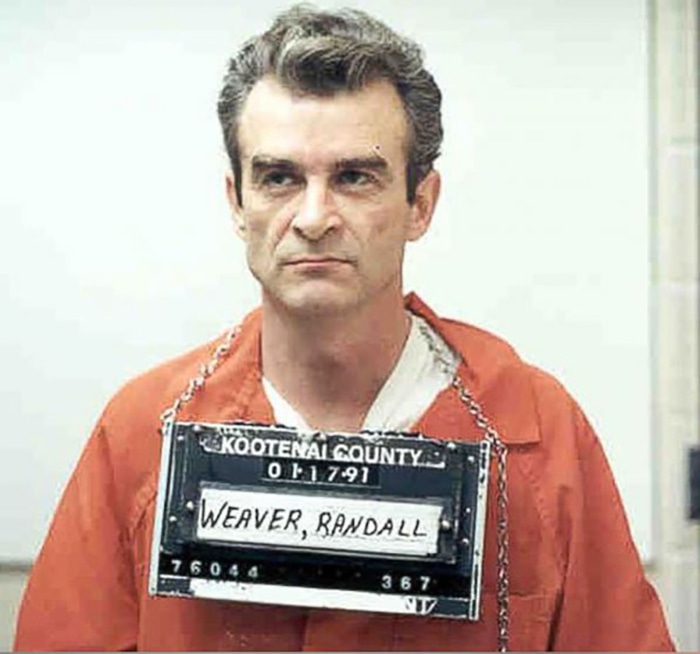

In December 1990, a federal grand jury indicted Weaver on firearms charges, and in January 1991 ATF agents arrested him following a ruse where they posed as stranded motorists. When Weaver failed to appear at court dates, warrants for his arrest were issued and passed to the U.S. Marshals Service (USMS).

USMS officers made several failed attempts to arrest Weaver peacefully between the issuing of warrants and the standoff, including one in which they posed as real estate buyers. The fugitive was aided by the remote location of his cabin, his store of firearms, and the credibility of his threats to defend his property with force. Between March and August 1992, the USMS settled for placing the property under constant surveillance.

The Weavers’ interactions with the government fueled their paranoia and pushed them toward further extremist affiliations, including Randy's quotations from White Power terrorist group The Order in written exchanges with the government. During this time, the family was close with Militia of Montana leader John Trochmann, whose family often brought supplies to the Weavers as they holed up at their cabin trying to avoid Weaver’s arrest.

On Aug. 21, 1992, the armed siege began after an encounter between Samuel Weaver, his friend Kevin Harris and a USMS reconnaissance team developed into a firefight and ended in the deaths of Samuel Weaver, Degan and Striker, the Weavers’ dog. Idaho's governor declared a state of emergency in the county, and a large contingent of local, state and federal law enforcement attended the scene. The following day, an FBI sniper killed Vicki Weaver, and wounded Randy Weaver and Kevin Harris.

As news of the standoff spread, a host of extremist figures rallied around Weaver. At the height of the siege, a group of 300 extremists of all stripes had gathered at the scene, including racist skinheads who tried to sneak in semiautomatic weapons to the Weavers. Militia figure Bo Gritz was called in to negotiate and gave the crowd a Nazi salute on his way back from meeting with Weaver.

Harris surrendered on Aug. 30, a day before Weaver emerged from hiding with his daughters. The men were later charged with the murder of Degan but were acquitted on all charges except the original firearms charges. Weaver was fined $10,000 and sentenced to 18 months in prison. After being credited with time served, he spent an additional three months in prison.

The nascent antigovernment militia movement adeptly exploited the tragic events. On Oct. 23, 1992, the so-called “Rocky Mountain Rendezvous” in Estes Park, Colorado, brought together representatives of a range of far-right factions to discuss the events at Ruby Ridge. The gathering – which included everyone from Second Amendment activists to White Power groups – established a strategic trajectory that elements of the far right have followed for decades.

The siege at Waco, Texas, the following year, which ended in the deaths of 76 Branch Davidian adherents, including 26 children, compounded the impact of Ruby Ridge on the surging far right.

In the fallout over the Weaver standoff, the U.S. Senate took up hearings on the events and a GAO (Government Accountability Office) report was published reviewing the federal actions. This led to more strict written standards of the use of deadly force. In 1995, both the Weavers and Harris were awarded settlements by the federal government.

As the 1990s wore on, federal agencies appeared to have learned from the deadly sieges at Ruby Ridge and Waco. On June 14, 1996, the FBI brought an 81-day standoff with the Posse Comitatus-descended Montana Freemen to a peaceful conclusion.

Along the way, they refused assistance offered by Randy Weaver, now free from prison, in ending the impasse.

In the years after Ruby Ridge, Weaver spoke in support of various far-right actors and causes. In 2007, for example, Weaver traveled to New Hampshire to speak publicly in support of tax protesters Ed and Elaine Brown, who were later arrested by federal authorities and eventually went to prison, had voiced antisemitic and pro-militia views.

However, he largely avoided taking an active part in far-right movements, content to function more as a symbol and a figurehead.

Among hundreds of books and documentaries considering the events at Ruby Ridge were a couple by Randy Weaver. With his daughter Sara, in 1998 Weaver published The Federal Siege at Ruby Ridge. In 2003 he partnered with Richard Mack, extremist leader of the Constitutional Sheriff movement, to write Vicki, Sam, and America: How the Government Killed All Three. Sara wrote Ruby Ridge to Freedom in 2012.

In death, Weaver and Ruby Ridge are still inspiring some of the most dangerous political currents in America. In the wake of the announcement of his death, far-right actors and conspiracy theorists took to social media to praise him as a hero and a martyr, pledging to carry on their various causes in his name.